It took me the better part of two decades to finish college, for example.

I married at twenty, quitting college with a year and a half of coursework in general studies and theater arts. My boys were born. My husband completed two degrees needed for his work. I took a variety of jobs, all the while wanting to return to college myself, taking a class or two whenever and wherever I could. Sometimes I dusted off the old textbooks and plays, reread portions, dreamed of going on with my education.

When my younger son started kindergarten, I took a part-time reading remediation position that became full-time, until the program was cut after a couple of years.

“I’d like to keep you on, if you’re willing to take a teaching assistant job in first grade,” my principal told me. “Furthermore, there’s a distance education cohort beginning for paraprofessionals to get teaching degrees. You should pursue this – you’d be an excellent teacher.”

I pondered the prospect. A teacher. At the elementary level? I don’t know. High school English, maybe, but . . .

“It’s a consortium,” the principal went on. “If you’re a full-time teaching assistant, our county qualifies you to attend with financial aid. The books are even covered.”

Here it was, the long-awaited chance to finish school, only it didn’t look exactly like what I imagined.

The principal noted my hesitation. “It’s a perfect opportunity. What are you waiting for?”

Turns out that the program had K-12 reading certification built in.

That was the tipping point.

I love roller coasters. They climb and climb, gaining momentum, then – wooooosh. Hold on tight, as you don’t know what’s coming next – a pretty good metaphor for the wild ride of life. I applied to the program, got in. I loved my classes, my advisor, my instructors, my classmates. Returning to college was exhilarating.

Until.

“Of course, as a full-time teaching assistant in our county,” my principal said, “you’re required to get bus driver licensure.”

WHAT?

I’m not overly fond of driving in the first place. The idea of maneuvering something as big as a bus, loaded with kids, being the only adult responsible . . .

“I’m not sure I can do it,” I said, going cold and clammy. My stomach lurched like it does after a sudden twist on a coaster, only worse.

The principal smiled. “Yes, you can. Look at it as something that gets you where you want to go.”

That’s what it came down to. If I wanted to finish school, to teach – which I now wanted to do more than anything, the ultimate situational irony – then I would have to face the big yellow monster.

My dad had driven a school bus when he was in high school. So had his sister. Back in their day, students were drivers. Daddy told stories about students tampering with the governor so the buses would go faster – I could envision the buses bumping down the country dirt roads, whipping around the bends in thick clouds of dust, kids bouncing wildly. He told the tales with glee; I listened in horror. While I darkly imagined Daddy’s great amusement on learning that I’d be driving a bus, if he’d lived to see it, this connection to him helped, if only the tiniest bit.

Look at it as something that gets you where you need to go.

I couldn’t let a bus stop me from finishing school or embarking on a whole new career that stretched out before me, glimmering and beckoning like the sea.

I signed up for the training.

The trainer started off with lots of stories, such as a driver once tipping a bus over by trying to avoid a squirrel, which is why we should never swerve if an animal runs in front of the bus.

I put my head down on the desk.

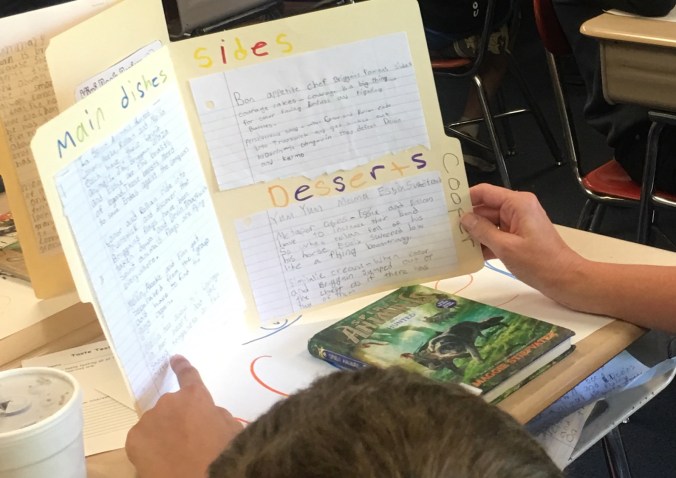

Then there was the first exam: Memorizing all the parts of the bus, how these parts are connected, what these parts do and why, what every light means. This was conducted by walking with the instructor, pointing everything out and giving an oral explanation. A written exam was also given.

I briefly considered failing these exams but my pride wouldn’t let me.

The training culminated in behind-the-wheel practice with the instructor, who asked: “Ever driven a Mercedes before?”

“No sir,” I answered.

He chuckled. “You’re about to now.”

I thought he was joking.

He wasn’t.

The bus I learned to drive on was made by Mercedes-Benz – who knew? It almost drove itself.

I managed to get this monstrous thing, this almost-airplane, through the narrow tree-lined streets of the nearby little old southern town without doing harm to anything until the instructor said: “All right, make a stop. Let these imaginary kids off the bus.”

I made the stop, opened the bus door. The flashing lights came on, the stop sign came out. I even counted imaginary heads.

For the first time, I thought: I’ve got this. It’s not so bad.

Then, as I closed the door to move on, the instructor said, “STOP!”

“What?!” I jumped a little in my seat. I stood on the brake.

“You just ran over a child,” said the instructor.

“I – what? How? I counted all the imaginary heads!”

“You didn’t check your mirrors. Kids can hide close to the bus and you’ll never see them if you don’t check all those mirrors. That’s why they’re there. Kids have been killed that way.”

I returned to work that afternoon in the deepest funk. A teacher assistant colleague greeted me: “Hey, how’d the training go?”

I sighed. “Not great. I ran over an imaginary child.”

My colleague grinned. “How did the imaginary parents take it?”

I laughed in spite of myself.

Still, I put myself on the prayer list at church. Seriously. The youth minister consoled me: “Look, when the time comes, God will give you driving grace.”

He was right.

The first time I had to drive, on my own, with real kids, it wasn’t a magnificent Mercedes bus but an old “cheese box,” as the kids say. I boarded with driving grace in my head and rosary beads in my pocket, given to me by a friend – and I’m not even Catholic.

I – and more importantly, the kids – lived to tell about it.

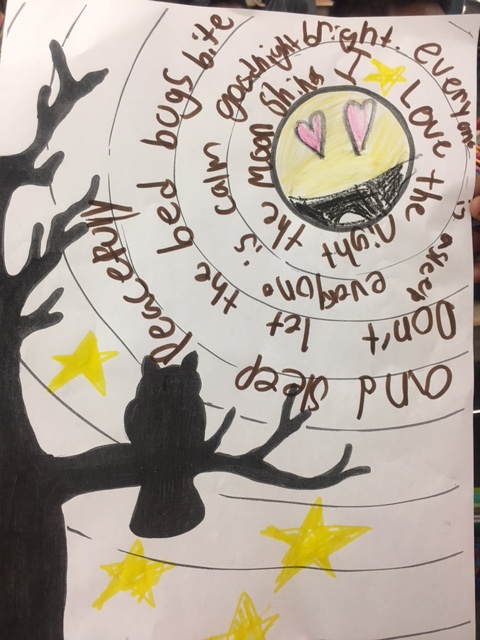

In fact, my driving the first-graders on their field trip to the movies (a trip of about three miles, consisting of three turns, one of which I took too close with a back wheel going over the curb, causing the bus to sway and the kids to scream), made their writing journals. When the teacher asked them to write about their favorite part of the trip, our entire class wrote various versions of this, with various spellings: “My favorite part of the field trip was when Mrs. Haley drove the bus.” On all the pages I was depicted at the wheel of the big yellow monster, my hair flying in the breeze for some reason, and smiling.

In the eyes of the kids, apparently, I was a great success.

I consider my mastery of the yellow monster my most dubious achievement, closely followed by my passing a college course on golf. No animals ever ran in front of me, all the kids got home, and other than the door handle rolling off one day and causing me to drive back to school with the stop sign out and all the lights flashing so that every car on both sides of the road pulled over, I am happy to report that I only had to drive a handful of times without incident until I finished the teaching degree and moved on, when I no longer had to drive a bus.

It did, indeed, get me where I needed to go.

Those obstacles that stand in the way of what we want, where we want to go – there’s no shortcut, no way over or around them. The only way is through, even when it doesn’t seem feasible, beneficial, or possible.

Whatever it is, whether it looms in front of you, in your past, or inside you, face your monster. Look it in the eye.

Then make up your mind to master it.

Grace be with you.