I write this final post of The Slice of Life Story Challenge from the passenger seat of my son’s car as we return home from an impromptu vacation.

This weekend’s weather forecast: Sunny skies, upper seventies—how could spring fever NOT strike?

“Let’s go to Busch Gardens,” said my son. “It would be good to get away and just have fun for a while.”

He didn’t have to say it twice.

Off to Williamsburg we went.

The area is home to me. I grew up going to this park, am still a diehard roller coaster fan. I expected just to have fun spending time with my youngest in the glorious, inviting weather.

—While trying to think of TWO MORE POSTS to write in this thirty-one day challenge.

We arrived Friday evening and decided to walk colonial Williamsburg in the dark. Mostly because we never have before, so why not?

Naturally one thinks of ghosts. In fact, several ghost tours seemed to be in progress. Guides carried lanterns, told stories in hushed tones to huddled groups of tourists. Once or twice, as my son and I passed the little closed shops with their wordless, pictorial trade signs hanging out front, or little wooden gates slightly ajar, with paths leading through herb and flower gardens, or caught a pretty strong whiff of horse and stable in spots, it seemed we were eerily straddling Time. One foot in Now, the other in centuries past. A shivery, delicious feeling.

And those lanterns carried by the guides—Reminds me of Pa-Pa’s lantern. I just wrote about it.

Eventually my boy and I checked into our hotel room where the decor was, of course, in keeping with the colonial theme. On the wall by my bed hung this picture:

—The Continental Army! I have just been writing about them.

I felt a slight prickling on the back of my neck, but I didn’t pay it much mind. I crawled into the high colonial bed and typed the whole of yesterday’s post—on memory and being present in now and writing and my father—on my phone, before falling fast asleep.

I woke this morning to a day tailor-made for adventure, exploring, celebrating. As beautiful as a day can get. My son and I made our roller coaster circuit at the park, where flowers were riotous beds of color by the walkways and the sweet fragrance of fresh mulch stirred in me, as always, some nameless desire. I do not know what or why. Something so organic, clean, nurturing . . . .

My son asked at lunch: “What are you going to write after this March post challenge is over?”

I told him my ideas, many ideas. He listened with rapt attention.

“Do it, Mom. Do all of it.”

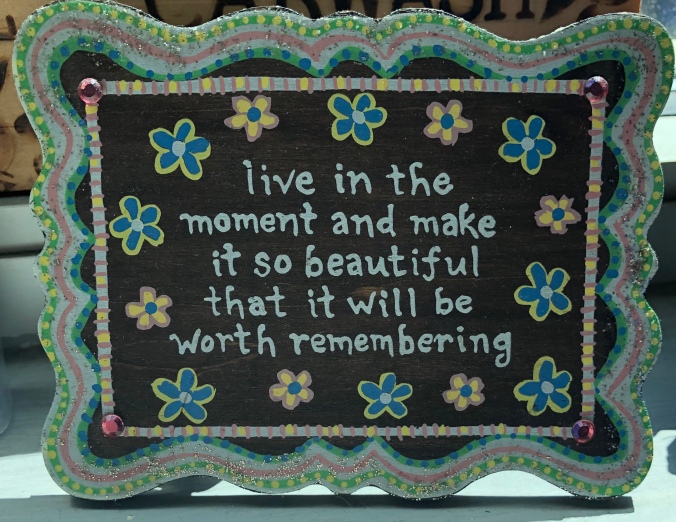

We finished our lunch, began another round of rides, when I caught sight of this:

“I JUST WROTE ABOUT SEEING AN EAGLE!” I exclaimed.

Passersby looked at me oddly.

My son laughed. “I know. The one by the road that flew away before you could get a picture. Well—now you can.”

There’s something in all this, I think, as I get my eagle photo. I don’t know what, but something.

We leave the park with one last stop to make.

My son wants to visit his grandparents’ graves.

Both sides are buried in the same veterans’ cemetery. We spend a few moments at each.

The last, my father.

Wrote about you last night, Daddy. Remember when I broke my arm in fourth grade and you brought my old doll to the orthopedist’s office? I could see it all like it just happened yesterday.

It occurs to me then that I’ve also just written about my house finches returning, generation after generation, to build their nest again on my front door wreath, a post I called “The Homecoming.” Like the finches, the next generation and I have just returned to the place where those before us carved out and sustained life. Where they now rest from all their labors.

—The baby finches, I should add, that my son and I named Brian, Dennis, and Carl after the Beach Boys, my musical son’s current passion. On this trip we’ve listened to their songs all the way up and all the way back, and as I write these very words, what should be playing in the background but “Sloop John B”:

Let me go home, let me go home

I want to go home, let me go home

“You know,” I say to my son, as daylight fades into night with just a few more miles until we really are at home, “this was a great trip. I am almost finished with the last post and can’t help thinking how these two days were like some weird recap of all I’ve written this month. Almost like that old, old, TV show, This Is Your Life—except that it would be called This Is Your Writing Life.”

“That’s how life is, Mom. So weird, sometimes.”

“Well, that’s basically why I write in the first place. To interpret life.”

I think for a moment, then add: “And because I am deeply grateful for it.”

—We are home. I need to check on Brian, Dennis, and Carl before going to bed:

—All snug. Goodnight, little songbirds.

They will be here so short a time; soon they’ll fly—OH!

I failed to mention that I got a “Happy Blog Anniversary” notification from WordPress that thanked me for “flying with them.”

Lit Bits and Pieces is three years old.

Three happens to be a number signifying completeness. Interesting to contemplate as the daily Slice of Life Story Challenge ends with this post.

I think of my fellow Slice bloggers, friends, fellow sojourners, how we all gathered at Two Writing Teachers for just a little while each day.

Now we fly on.

But that’s only the end of this journey. The end of a thing is only the beginning of another.

—Write on, writers. Keep tasting life, exploring the meaning of your days.

Keep spreading your wings.

Fly high.

And far.