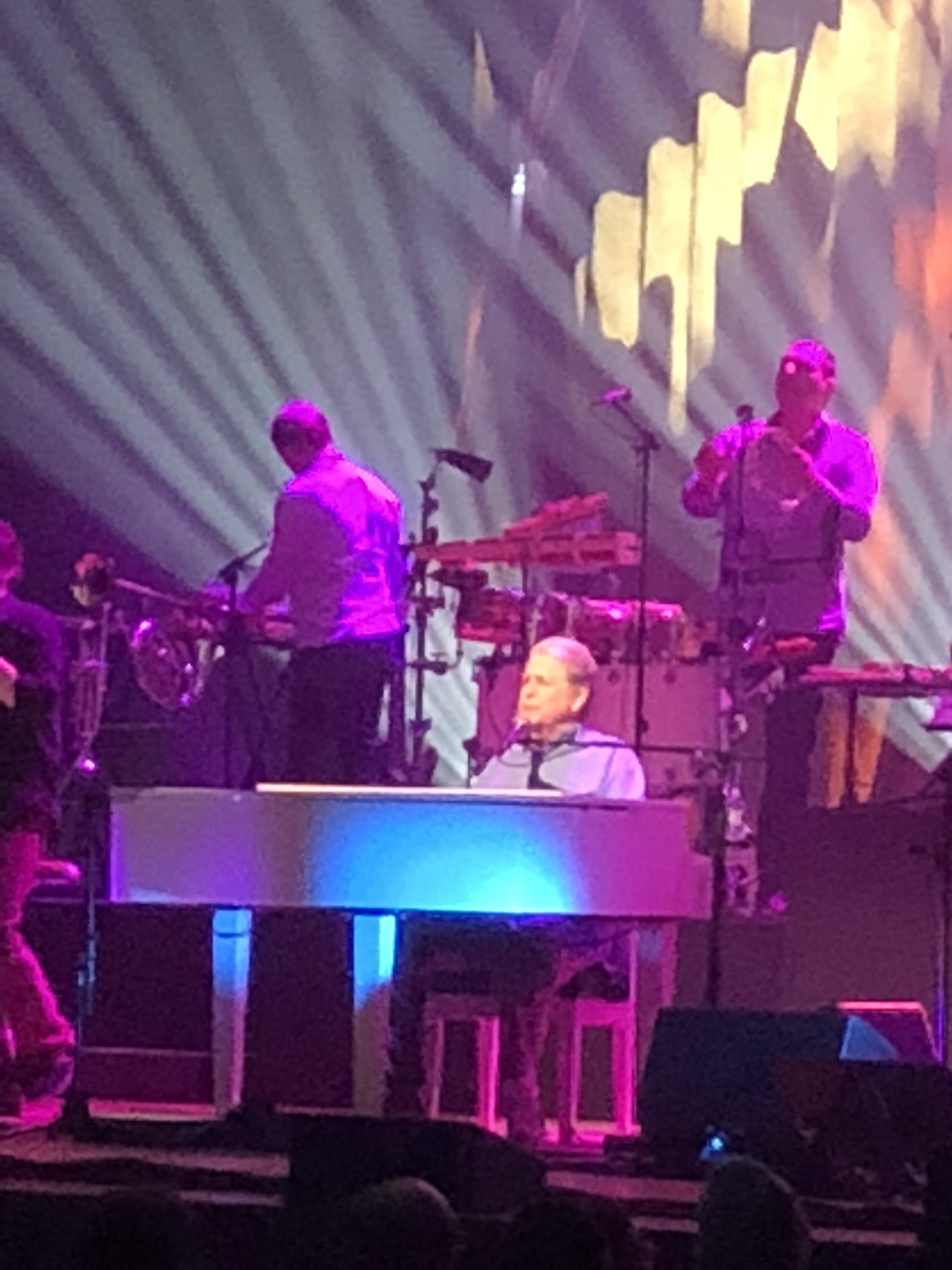

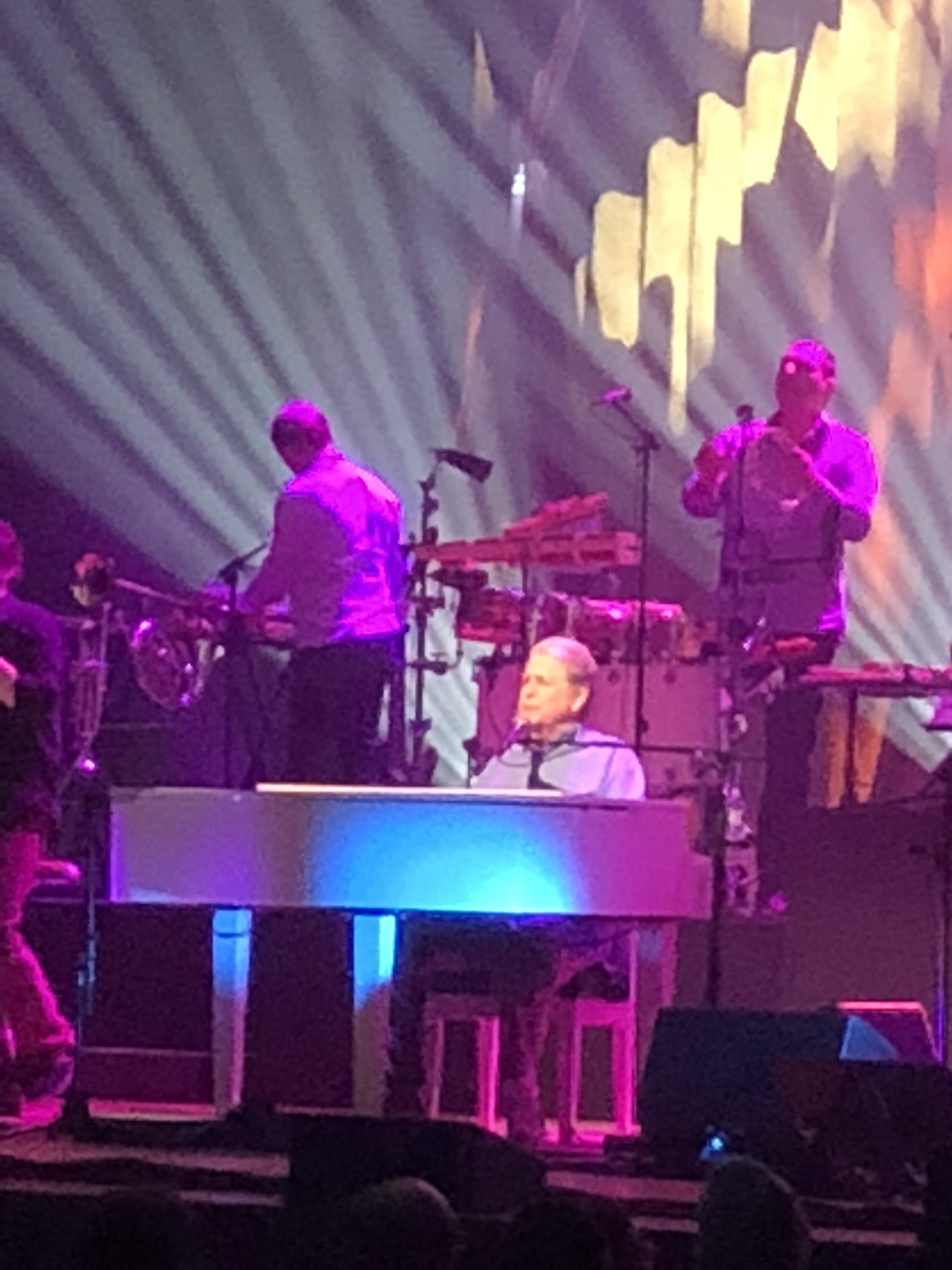

Brian Wilson sings his favorite song from Pet Sounds, “God Only Knows.” 11/02/2018. Richmond, VA.

If setting is everything, then tonight is mystical.

To begin with, the November evening is balmy. Few people in the crowd gathering on the sidewalk are wearing jackets. There’s quiet anticipation in the air, in the murmur of voices. It’s supposed to be raining but the sky above the city is dry, shimmering like a thick swath of navy blue velvet.

The sense of wonder deepens upon entering the auditorium. I’ve never been inside the Carpenter Theater in Richmond before and am unprepared for the splendor of it. Gilded walls, pillars wrapped in vines, balconies adorned with Roman statues, backlit alcoves with busts—it’s like stepping out of a time machine into Old World fantasyland. Overhead, white clouds frame the stage front against the dark auditorium sky —ceiling, I mean—where dozens of man-made stars sparkle an ethereal welcome.

The writer in me searches for words:

breathtaking

otherworldly

adventure

expectancy

Apropos, I think, for our temporary raison d’etre: My family is here for the Brian Wilson Pet Sounds concert.

Primarily because the younger of my two sons (Cadillac Man), at twenty-one, avows Brian as the artist he most admires. He strives to emulate him in his own music. He studies how Brian deconstructed songs and what he did with vocals and chord progressions, complex, innovative stuff fifty-two years ago when Pet Sounds was released and still the stuff of legend, of music history. My son researches the Beach Boys and tells me things I never knew about their origins, talents, trials, and tragedies. He identifies with Brian on multiple levels—they both have a penchant for Cadillacs, both of their fathers lost their left eyes—but mostly my son relates to Brian’s musical thought and language. Cadillac Man confesses that he couldn’t concentrate on what his first grade teacher was saying in class years ago because “Sloop John B” was playing in his own head. This explains a few things about his childhood academics . . . nevertheless, that this incident occurred nearly four decades after the release of Pet Sounds speaks to the timelessness of Brian’s work.

So we’re here to see an icon tonight. A glimpse of the extraordinary.

For me it’s not just the music, although I’ve always loved it, too.

It’s the story.

A boy deaf in one ear, teaching his younger brothers the harmonies he heard in his head, singing together in their bedroom at night. An athlete who once wrote in a high school essay: “I don’t want to settle with a mediocre life, but make a name for myself in my life’s work, which I hope will be music. The satisfaction of a place in this world seems well worth a sincere effort to me” (I Am Brian Wilson: A Memoir, 2016).

A name for himself, a place in this world, and a life that’s anything but mediocre . . . I think about these things as the crowd greets him with a standing ovation. Brian is helped onstage, having had back surgery earlier this year. He wears a brace on one leg. His escorts seat him at a white piano, center stage, where his silvery hair glows in the spotlight.

I look at him and think about time. How quickly life passes. I think about the strange, sad, haunting truth of great gifts so often coming with equally great physical or mental afflictions attached, as if that’s part of the deal. We all have our demons. The ones that chase us, the ones that we chase. Brian’s battles are well-known. The most wondrous thing to me this night is that he’s still here, despite all, the only one of the Wilson brothers to reach old age, a survivor of so much. Still performing, sharing his profound gift.

He speaks just a little throughout the show. I wonder how he feels, what he thinks. At seventy-six, does he enjoy touring now? He wasn’t able to for years when he was young. Does anxiety still threaten to crush him? Is he in much physical pain?

If the answers are yes, then he’s mastered these demons. For the sake of the music, for others.

Brian sings his brother Carl’s solo in “God Only Knows” as stage lights come to rest on him like splintered sunbeams. God rays. I recall the clip of his speech for the Beach Boys’ Rock and Roll Hall Fame induction, in which he said that “music is God’s voice” and that he only ever wanted to create joyful music to make people happy.

He does just that, even now. At the end of the concert, this orderly, respectful crowd—comprised of multiple generations—is on its feet dancing to the old favorite songs. It’s a celebration of life, love, being young—whether now or long ago—and the creative power of humanity overcoming the terrible weight of being human. I think of these things as the audience thunders its applause, as Brian’s escorts return for him, as he’s carefully ushered away.

I wonder what it costs him, these moments of joy for other people. And marvel that he still has it in him to give.

I leave the theater mentally wishing Brian peace in the days and years remaining to him and to his loved ones. I hope he can keep doing this for as long as he wants. I ponder the curious nature of gifts and how they’re so clearly bestowed on certain mortals. Maybe the Roman auditorium put me in mind of the Muses. There’s a word for the strength to overcome, to relentlessly pursue and attain the beautiful, despite unfathomable suffering, the Herculean feat of living. I can’t quite think of what it is. Overhead, the real stars glitter at random through an indiscernible cloud cover. The night is soft, quiet. And then—there it is. The word. I am not sure what Brian would say, but to me, the street sign says it all:

*******

I must also mention the timeless charisma of Al Jardine in this performance. He carried much of it while seeming to enjoy every moment. As did Blondie Chaplin, with absolute showmanship. All in all, the instrumentalists and vocalists paid exemplary homage to the music, which sounded unbelievably rich and true performed live.