As a headmistress and co-founder of my school’s Harry Potter Club, I was recently admonished to take the Pottermore Patronus quiz, as all other Patronus quizzes are essentially heresy. I approached the task with a bit of trepidation, having heard of people attaining aardvarks and the like.

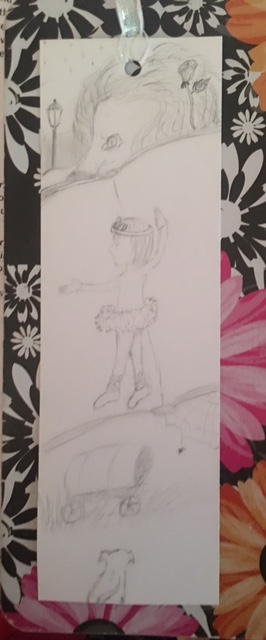

For the non-Potterite: The Patronus charm produces a silvery animal guardian, usually representative of the individual casting it.

Being a fantasy fan since childhood, and considering my headmistress role, it was necessary: I plunged into the virtual dark forest to seek my symbolic protector. On the site, ghostly words appear in groups of three amongst the trees; the seeker chooses one and is moved onto the next set. At one point in this quest, when I paused too long, the words evaporated with a reprimand: “You are too slow. This game requires quick reflexes.” Silently chiding myself for overthinking simple word choices, certain that this blunder would land me with an armadillo or caterpillar, I picked up my pace. At last, in the ominous forest, a silvery shape materialized.

A white mare.

Beautiful and powerful, my white mare galloped through the forest, luminous against the darkness. Enchanting.

My next quest, naturally, was looking up the symbolism.

From various sites, the synthesis is that a white horse represents wisdom, power, loyalty, heroism, nobility, victory – encouraging, yes, but also inversely raising an intrinsic, lofty bar: am I worthy of the white mare? Do I deserve her? Never mind the fact that I gained her by playing a game with an end product based solely on word choices, not short answers or soul-searching responses. The writer in me delves deep into the metaphorical.

I already knew that white horses can symbolize death or the end of the world. They are considered psychopomps, creatures that guide human spirits on their journey from Earth to the afterlife.

As I pondered these connections, my Patronus suddenly conjured up road trips with my father and sister. Three hours is an eternity to young children cooped in a car, so to pass the time, Daddy taught us a game he played as a child:

“When we go by any horses, if they’re on your side of the street, you get a point for each horse. If you have a white horse on your side, it’s worth ten points, because you don’t see many of those.”

My sister and I instantly glued our faces to our respective windows, for we’d been by these random pastures before. We’d often seen horses grazing, strolling, sometimes galloping. I was sure – I just knew – I’d get a white horse. Maybe more than one!

“The thing is,” Daddy continued, “if we pass a graveyard, and it’s on your side of the street, you lose all your horses.”

So we played the game. My sister and I gained horses with glee, then lost them with loud groans, without realizing that one of us would win on the journey to the destination and the other would win on the return trip.

Daddy drove on in peace, smiling to himself.

How many horses I won and lost, I’m not sure, nor do I recall how many were white, only that they were there by the wayside on a long, tiresome journey. Those white horses are obscured by time now, very dim, but still real, ever more priceless, in my misty memory.

Enchanting, indeed, that one should reappear as my guardian after so many years, and that I should have gained it in a game venue that didn’t exist when I was a child.

Daddy, I think, would be pleased. Perhaps he is, from his place on the other side.

Reflect: What creature might symbolize you, and why? I’ve often played a game with students, challenging them to think of an animal that begins with the first letter of their first names (I’ve always chosen fawn in these scenarios – perhaps I should change it to foal?). No two can be the same, so each student ends up with a unique animal and has to think of ways the animal might represent them or their lives. Think – and write.