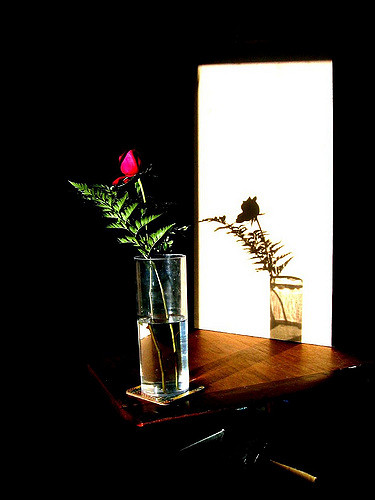

Land planarian. Pavel Kirillov. CC BY-SA

Granddaddy and I are walking around “the horn.” I am puzzling over why he calls this path “the horn.” When he says it, I know he means the journey from his house down the gravel road past the formidable, fairy-tale-dark woods with a tiny cemetery in the clearing, past unpainted houses in various stages of falling down, to the narrow paved highway and on around to the other side of this gravel road where, in a tiny screened-porch house, an old widow woman dips snuff, on past Grandma’s homeplace where her disabled brother lives alone and grows sunflowers that loom over my head, always turning their faces toward the sun, which is now obscured. It rained earlier in the day, breaking the blazing summer heat. The thirsty ground drank its fill; the rest of the blessed rain hangs invisible in the air, as heavy and warm as bathwater, and drips amongst the trees, where the birds are chattering against a background of crickets who think it’s night again, along with cicadas buzzing in such numbers that the earth vibrates with the sound. Granddaddy and I are on the last leg of “the horn,” passing his garden, a steaming, lush, leafy paradise that looks to me like an artist painted it with watercolors. We walk by the ditch bank where his scuppernong vines drape the trellis he built, past the line of pink crape myrtles curving along the edge of the yard, back to the sidewalk in front of the house where we started.

Granddaddy stops to get the newspaper from the box and I go on ahead—

“Granddaddy!” I shout, for he’s hard of hearing, although Grandma says he hears what he wants to. “What is this?”

There on the damp sidewalk, headed toward the house, are three long worms, side by side. They are tan like earthworms, but many times longer than any earthworm I’ve ever seen. Maybe a foot long. Their skinny bodies undulate like snakes; they glide over the cement holding up their big, almost-triangular heads.

Granddaddy comes near, leans down.

“I don’t know,” he says after a moment. “I ain’t never seen anything like them before.”

I’m stunned. Granddaddy has farmed all of his life, except for the years he worked at the shipyard. He knows everything about the outdoor world, has told many stories of the things he’s seen, like a fully-formed tree growing underground when he had to dig a well once. If he doesn’t know what these worms are, they are strange indeed.

I look up at his pleasant, wrinkled face, shielded by his ever-present cap. His crinkly blue eyes are thoughtful. I wonder if he’ll kill these alien creatures, chop them up with the hoe like he does the copperhead who dares enter his realm.

But he pats my back: “Let’s get on in the house, hear.”

And so we do. I don’t see where these three hammer-headed worms go, and I never see them or anything like them again.

The worms resurfaced in my memory recently; I’d almost forgotten them. If the Internet had been around at the time, Granddaddy and I could have learned within seconds that these were land planarians—toxic predatory monsters that destroy the ecology of a garden by feeding solely on earthworms, the great garden benefactors that aerate the soil and add rich nutrients. Planarians aren’t native to the United States; they hail from Asia, so a remaining part of the puzzle is how they ended up in the far reaches of rural, coastal North Carolina.

This story isn’t really about the planarians, however. It’s about my grandfather, infinitely wise despite having quit school in the third grade to work on the family farm. A man who used the phrase “the horn” which I have just now learned is a mathematical synonym for a cornicular angle, which, yes, describes the country path we walked (new question: How did he know?). My grandfather saw something he’d never seen before, these three worms. He analyzed them carefully. He let them live, not knowing they could do harm to his garden. Which ended up being the best choice, for if he’d smashed them or chopped them up, every piece would have grown into a new planarian. He would have thereby ensured the destruction of his garden and its bounty, which benefited his whole family. He would have, essentially, spread the poison.

The lesson I take away from this long-ago surreal encounter is First, do no harm. In pretty much any situation. Analyze. Evaluate. Proceed with caution and discernment. Consider long-range ramifications; if they cannot be known at the moment, forbear. Poison is often invisible; be wary of tapping into it, spreading it.

Point to ponder: What are the planarians of your own life and work? What threatens to destroy what’s valuable? To answer that, you must define the garden, the earthworm, and their relationship. I speak as an educator. As a wise old farmer’s granddaughter. For me, metaphorically, the garden is not humanity itself, but something which springs forth from the human spirit—organic, beautiful, beneficial. In a sense, teaching (or writing, as I clearly do that also; think about your own work and how it applies here) is about being the earthworm, aerating the growing ground, devoting yourself to developing the richness and nutrients needed for the collective good of those who follow, that they might also produce that which is beautiful and beneficial. Harm comes in the form of anything that would limit, stunt, or destroy this exploratory, creative, thriving growth process. Planarians attack and destroy their own kind for their own benefit. We don’t always know them when we first see them, for they resemble that which is good. Not everything has a noticeably triangular head. Watch, analyze, evaluate, discern over time. Avoid blindly buying into the toxicity, the very thing that counteracts and defeats all your best efforts, and multiplying it.

First, do no harm.