In 1906, Theodore Roosevelt was president, Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, and the San Franciso earthquake killed around three thousand people. The Panama Canal was under construction and Cuba had its first president. Susan B. Anthony died that year. Lou Costello, Estée Lauder, and Anne Morrow Lindbergh were born.

In the far reaches of eastern North Carolina, a farm woman named Claudia Amanda Victoria delivered another of her ten children. A boy. She would have only two girls; one would die of diphtheria at age four.

But this baby boy would be hardy. He would outlive them all.

She named him Columbus St. Patrick.

Some folks called him Columbus. Those who knew him best called him Lump.

I called him Granddaddy.

As I grew up listening to the old stories, I tried to imagine living in his era. Seeing an early Ford Model T. Mail-ordering live chickens, delivered in wire cages by horse and buggy. Raising ducks that wandered off to the swamp on a regular basis, only to be herded back home again to eat bugs in the garden and to provide eggs for breakfast. Learning to plant and to harvest, to be in tune with the rhythms of the earth, following the steps of that ancient choreography, the seasons.

He was five when the Titanic sank, seven when World War I began. His older brother, Jimmy, served in the Great War and returned; I would know him and his wife Janie in their old age. They lived in a little tin-roofed house along one of the many dirt roads of my childhood summers. Jimmy and Columbus had a brother who drowned long before my time. Job Enoch. One brother accidentally shot and killed another on the porch of the family home. I knew their sister Amanda, who had a high-back pump organ adorned with brown-speckled mirrors in her house. The organ sounded and smelled of ages and ages past…but she could play it, and she could sing.

Columbus didn’t sing, but he loved country gospel songs and bluegrass to the end of his days.

And Columbus St. Patrick loved Sunday School. He had perfect attendance for years, garnering long strings of pins awarded to him. He did not enjoy regular school. He quit in the fourth grade to work on the farm. Later in life he had some regrets about this. But his father walked out on the family and Columbus rose to the role of provider.

He participated in community hog-killings, with the farm wives taking the backbone to flavor collard greens. The pork was preserved in barrels with salt brine. Some of the folks enjoyed scrambling hog brains into their breakfast eggs.

Columbus St. Patrick worked hard. He plowed fields with mules. He took part in the making of molasses, which required several people. Mules walked in a circle, harnessed to poles attached to large grinder where sugarcane was fed to extract the juice. The juice would be collected and heated in trays over a fire, skimmed numerous times until it became rich, blackstrap molasses. At the end of a meal, he sopped his biscuits in molasses, and poured his hot coffee in the saucer to cool it.

He competed with a scrappy little woman named Lula for the honor of being the community’s top cotton-picker. She often beat him.

Lula would be widowed when her husband Francis hung himself in the woods. One of their daughters would find his body.

Columbus St. Patrick’s youngest brother married another of those daughters.

Columbus made some time to hang out with the young people, attending taffy-making parties in their homes and driving groups of friends to the movies in town…all the while noticing Lula’s daughter with the wavy blonde hair and straight posture. There was a certain spark about her.

She considered him her mother’s friend. The “older” set. She was nine years younger and she had her eye on the preacher’s son, who would surely follow in his father’s footsteps: How wonderful, to be a preacher’s wife!

It didn’t happen. Desires of the heart sometimes come to unexpected fruition: I would be a preacher’s wife, a half-century later.

This daughter of Lula’s ended up marrying a farmer: Columbus St. Patrick. They planned to wed in September but he had the mumps. And so it came to pass in mid-December instead.

My grandparents.

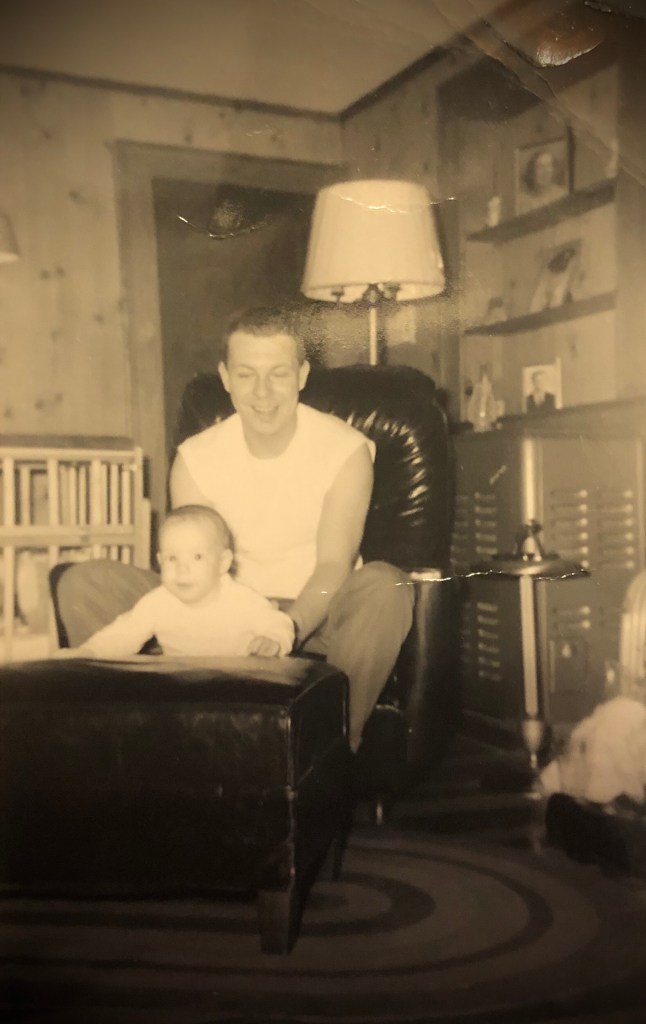

Here’s a photo taken sometime early in their marriage:

Ruby Frances and Columbus St. Patrick, circa 1937–1938.

She would have been around 23. He would have been 31 or 32.

If this photo was taken prior to October 1937, my father was not yet born.

They would endure the Great Depression and the second World War with a small child. My father. When Columbus St. Patrick couldn’t make a go of tenant farming and sharecropping, he traveled to the shipyard nearly 200 miles away with a group of men from down home. He was working there, building cradles for ships, when Pearl Harbor was attacked. Suddenly U.S. ship production went into overdrive; the Yard turned out ships in three months versus the usual year.

He would try, after the war, to make a living farming, painting, and doing other handyman jobs. By that time there were three children to care for. Columbus opted to go back to the shipyard, staying in a boarding house during the workweek and coming home to see his wife and children on the weekends.

For ten years.

His son (my dad) became senior class president and entered the United States Air Force after graduation. The oldest daughter was a high school basketball star; Columbus St. Patrick nailed peach crates to posts out in the yard for her to practice. By the time his youngest daughter was ready for high school, he’d had enough of separations. He moved the family to an apartment near the shipyard.

Hilton Village, built between 1918 and 1921, is the first federal wartime housing project in the U.S. It was created for shipyard workers. These quaint, English-style rowhouses would be the setting of my first memories. I would awaken in the dim gray morning at my grandparents’ upstairs apartment and my grandmother soothed me back to sleep while my grandfather, having risen at four, made his own breakfast before going to work. On Sundays, his day off, he took me to the playgound behind the Methodist church.

I felt as safe as I ever have in life, walking hand-in-hand with him.

He retired after I started school and lived another twenty-nine years. He saw my children. He survived the removal of his bladder after a cancer diagnosis. My grandmother would empty the urostomy bag and dress his stoma (surgical opening) every day until his death.

They would lose their middle child, their basketball star, to multiple sclerosis in her fifties. She died on Good Friday; they buried her on Easter Sunday. Their son (my dad) was just recovering from bypass surgery after his first heart attack. He would not survive the second, but Columbus would not be here to suffer the loss of his son.

Granddaddy died of lung cancer under hospice care, at home his own bed, as he wanted, on a fine spring day. He refused morphine in favor of keeping his mind clear. And it was, to the very end.

St. Patrick’s Day rolls ’round again and stirs all the memories. They spring to life, as rich and sweet as molasses that Granddaddy and I sopped with our biscuits. He was always embarrassed by the oddity of his middle name. I am proud of it. I have loved it all my life, just as I’ve loved him. Fiercely. I have learned many a valuable lesson from Columbus St. Patrick: Treat people well. Help those in need. Money doesn’t buy happiness (back in the old days, he said, nobody had any money but everybody was happier). Love your family. Love your neighbor. Get a dog to love. Work hard. Persevere. There’s always a way. Tend the earth. Do your duty. Spend time with children, for they are precious. Go to church. Trust in the Lord. Return thanks.

One day, he said, we will meet again in a better place. I am looking forward to it.

Me, too, Columbus St. Patrick.

Me, too.

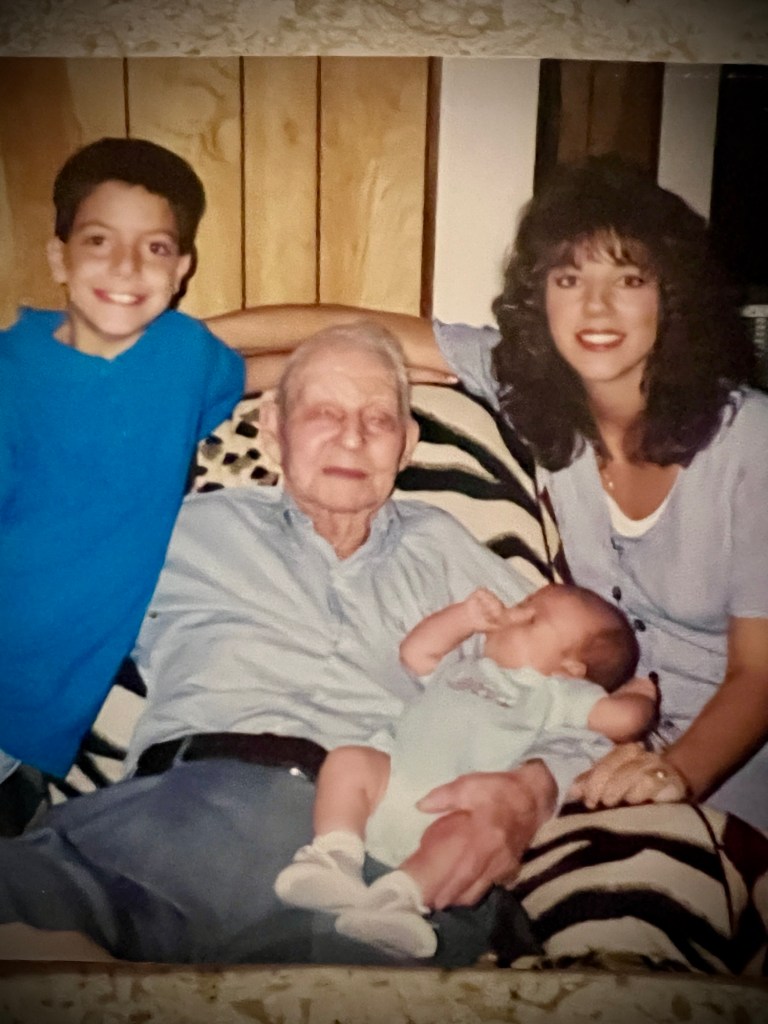

My boys and I visiting Granddaddy for his 91st birthday, 1997.

My youngest was six weeks old.

*******

with thanks to Two Writing Teachers for the March Slice of Life Story Challenge