part of a story-poem memoir, when I was nine

The pediatric wing

of the hospital

is quiet

in the gray-blueness

of a June afternoon

easing into dusk

muffled sounds and voices

from the nurse’s station

down the hall

alone in my room

my newly-casted arm

is heavy

and awkward

bent in a Z-shape

so the bones

will knot back together

nicely

on the bedside table

two dozen handmade cards

crayon-decorated

by my fourth-grade classmates

brighten the sterile room

Hope you are feeling better SOON!

I’m sorry about your arm

We miss you

I am feeling

surprisingly loved

in these

long and lonely

moments

of nothingness

until a scream

shatters the

gray-blue stillness

a jolt

of electricity

shoots through

my heart

another child

nearby

the scream rises

and falls

into loud sobbing

it goes on

and on

when the nurse comes

to take my vitals

I ask

Who‘s that, screaming

she replies

while taking my pulse

Another patient

across the hall

he’s five

What’s the matter with him

Why is he screaming

like that

she looks at me

I can see

she’s thinking

His foot was crushed

by a lawnmower

He is frightened

and he has a rough road

ahead of him

would you like

to go see him

it might help him

to not be so

afraid

I’m imagining

a little foot

full of crushed bones

how can doctors

ever put all the pieces

back together

it frightens me

I don’t want

to see

but his screams

are terrible

to hear

Okay

I say

I will go

although my heart

is beating

no

no

no

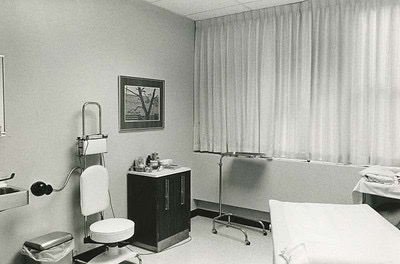

Pediatrics exam room. Stanford Medical History Center. CC BY-NC-S