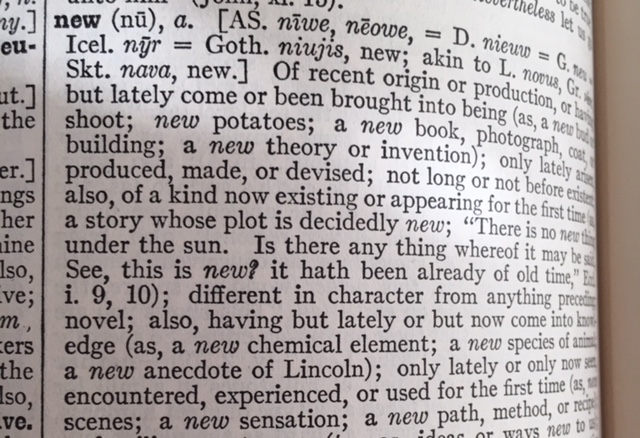

In reflecting on my reading and writing life, I am most thankful that my tastes cover a pretty wide spectrum. As a child I devoured everything from Dr. Seuss to Highlights, from cereal boxes to Funk and Wagnalls Medical Encyclopedias (yes, really), from fiction series to biographies, from Reader’s Digest to dictionaries, as I marveled over the many meanings a single word can have.

None of these were required reading in school.

All of this is what I chose to read, was compelled to read, from an insatiable hunger for the experiences, the ideas, the information, the emotions, the beautiful and the stark way of stringing words together, long before I thought about how hard authors work on hammering those words and phrases into something with just the right impact on readers.

Now, as a writer, my tastes run the gamut as well.

With Lit Bits and Pieces, I am usually reflecting on or exploring meanings of every-day experiences. Creative nonfiction, mostly.

Today I am sharing a short piece of fiction – for, truthfully, fiction is forever beckoning me with a capricious and winsome smile.

This was inspired by a personal challenge, a house I once lived in, and being told a long time ago that when she was a little girl, my maternal grandmother sometimes assisted her midwife mother.

-Enjoy.

Beacon

The captain’s wife was going to die.

Lily and her mother couldn’t save her.

They tried.

Vestal administered tinctures she’d made from leaves and bark as six-year-old Lily rubbed Miss Rebekah’s swollen belly, repeating over and over in her mind like a mantra: Little baby, please get borned . . . your Mama’s trying so hard.

Lily’s arms ached. The odors of sweat, blood, and tincture hung heavy in the close room. Miss Rebekah had chosen the highest, hottest point in the house and she couldn’t be moved now. Lily breathed through her mouth instead of her nose to avoid the metallic taste of blood and salt on her tongue. She kept kneading: Little baby, please, PLEASE get borned . . . .

The hours wore on; the sky darkened and thunder rolled in from the Atlantic.

Storms frightened Lily. Vestal said she mustn’t let it show. “When you live by the ocean, Lily dear, storms are always violent. Become accustomed to it. This is where thunderstorms are born, child.”

The wind moaned like a ghost under the eaves; rain slapped against the windowpanes. Lightning burst and sizzled a split second before the thunderclap shook the house. Lily jumped but she didn’t cry out. She sat trembling while Vestal calmly lit the kerosene lamp on the dresser.

Rebekah, sinking deeper in the feather bed, whispered, “Miss Vestal, would you move that lamp over to the window, please, so Captain Turner can find his way home.”

Captain Turner was at sea. Lily knew he wasn’t due back any time soon. Even if he was, he’d never see this lamp through the storm.

Vestal hesitated.

“Please.” Miss Rebekah’s whisper was barely audible, more air than voice.

Vestal carried the lamp to the sill of the window overlooking the widow’s walk. Beyond her mother’s silhouette, Lily could see the surf illuminated by lightning, billowing, foaming, crashing. Lily thought about the women at the marketplace who dressed only in black, murmuring to one another that this Carolina coast was treacherous even without storms.

Women who had watched for ships that never returned.

Rebekah groaned. Vestal flew back to her. The groan was so deep and prolonged that Lily’s courage finally collapsed. She cowered with her hands over her ears while Rebekah, just nineteen, married less than a year, made one last, valiant push before her life ebbed away. Lily knew it was all over when Miss Rebekah lay silent, her pinched face turned slightly toward the window where the lamplight flickered, then stood still.

Vestal gasped: “Lily!”

Lily scrambled to the foot of the bed. There in her mother’s hands was a tiny, motionless body. In all the births she’d witnessed, Lily had never seen anything like this.

The baby had no face.

“Oh, Mama, what’s wrong with it?”

“She’s a caulbearer! All my life I’ve heard of this! Cauls bring good luck, Lily, and healing powers. Whoever owns one will never drown. We must save it for her Papa.”

Lily watched as Vestal gently peeled the membrane, intact, from the baby’s face. Sweet-smelling fluid trickled from beneath the caul. When the veil lifted and she faced the world at last, the baby shuddered, reddened, flailed at the air; she drew a rasping, croup-like breath, then gave a mighty squall, startling Lily.

Vestal beamed.

Almost instantly, there was another sound: heavy boots pounding up the wooden stairs. Captain Turner burst into the chamber, rivulets of rain and seawater running from his hat and cloak, so out of breath he couldn’t speak. He simply sank to his knees on the floor in the circle of light cast by Rebekah’s lamp.

Lily was little, but she believed in miracles, believed that she was witnessing how many, right now? She eyed that lamp, glowing so serenely through the gloom. She knelt by the struggling captain. With a tentative hand, she dared to pat his arm:

“Welcome home, Captain. Everyone’s made safe harbor now. I think maybe you should call this baby Stormy, sir.”

As if in agreement, the flame in the lamp flared and danced.

******

Note: My original version of “Beacon” ended up placing in a flash fiction competition sponsored by Women on Writing – just one of the ways I’ve tried to push and challenge myself as a writer. Here’s their pretty fun response: The Muffin/Women on Writing Interview.