I found it in one of my old Bibles when I was preparing to speak at a women’s conference.

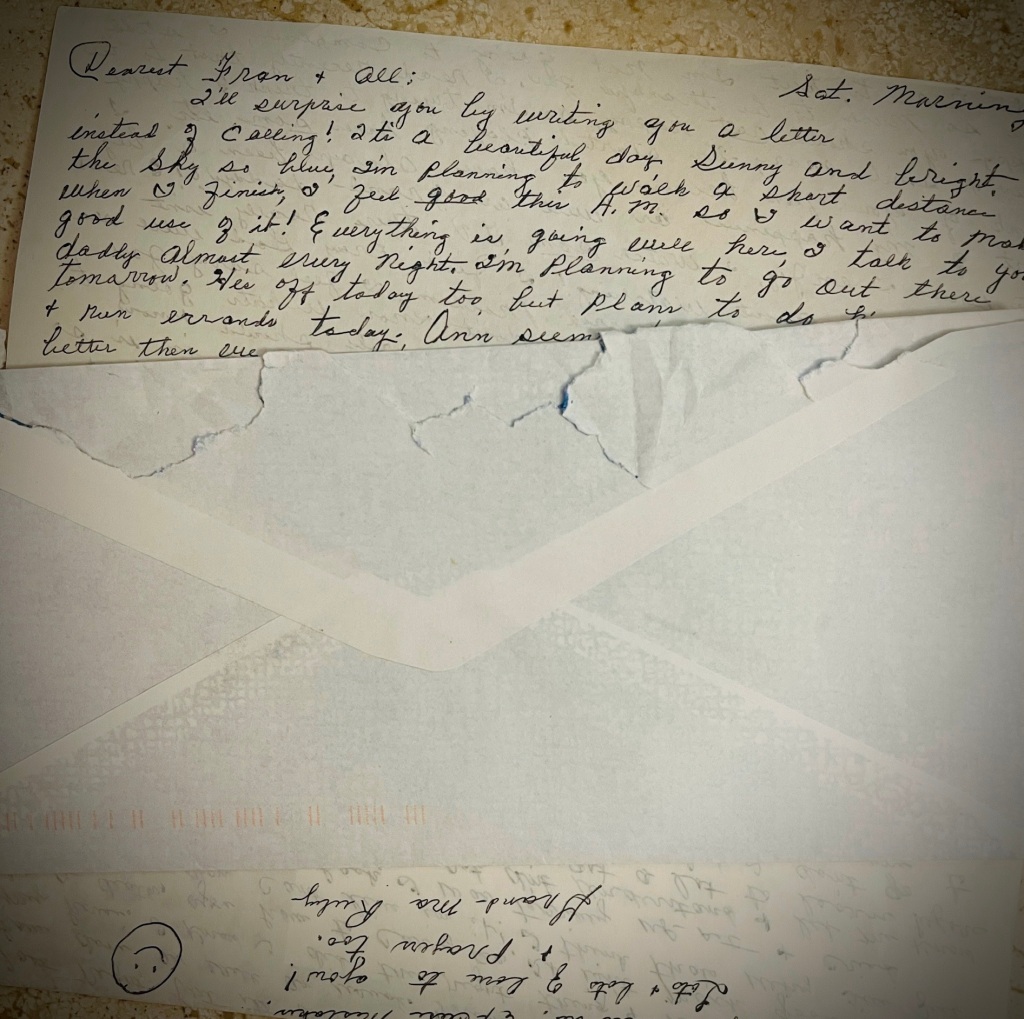

A letter from my grandmother.

Postmarked September 29, 2001…not long after 9-11. In the wake of what seemed the end of the world.

She wanted to surprise me with a letter. She’d written dozens to me throughout all the years we lived in two different states, since I was six. In her eighties, however, her fine penmanship had begun to look shaky on the page. She had taken to making phone calls more and more.

She writes of the beautiful day: sunny and bright, the sky so blue. I’m planning to walk a short distance when I finish and feel good…

She writes of family, that she talks to my daddy every night, and tomorrow she will see him. She writes that my mother seems to be doing good, better than we even thought! I no longer remember the context of this statement; my mother was frequently in poor health, in body and in mind.

She writes of my Aunt Pat’s moonflower, presently blooming, and asks if I remember her moonflower growing around the stump of Granddaddy’s pecan tree by the old dirt road and that she once had another by the pump house…its runners grew on the pump house, shrubs nearby, and the fence.

For a minute, I am there, walking in long ago, seeing the profusion of white blooms, breathing their perfume…

Then she tells me not to worry about her. She had given up her house and had come to live with my aunt; at 85, unsteady on her feet and occasionally falling, she could no longer live alone. She writes: I have accepted it, like a death. You have to carry on.

She admits to crying a lot at first. Then: I’m not going to complain. I still have so much to be thankful for. I read recently that to be happy, you should act happy, so I’m trying to think happy thoughts and smile more…I think of you often because you have always been a big part of my happiness as well as Grand-daddy’s!

She read books; she played tapes of gospel music; she prayed for God to see fit to take care of our world problems. She writes of violence and violent people not knowing what being happy is.

She misses her piano, her most-prized possession. She says that since she couldn’t take it with her when she gave up the house, she’s glad I wanted it: I hope it will bring much happiness to you and the boys.

She would never know that my youngest would learn to play on that piano, that he would become a phenomenal musician, that he would learn to sing all the harmonies in gospel songs, that he would eventually obtain a college degree in this, that he would lead choirs.

She writes that she hopes to see me and the children soon, even if for a little while, knowing I’d go visit my parents, too. She so wanted to spend time with my children…

She closes with her love and prayers too.

Two tiny notes are included also, one for each of my children, then ages twelve and four. In the note to the youngest she mentions hummingbirds…they will soon be flying to a warmer climate but will come back at Easter.

As I hold these written treasures in my hands, savoring every word, a little shadow flickers at the kitchen window. A hummingbird, coming to my freshly-refilled feeder.

A year to the day after Grandma wrote this letter, my father would die suddenly. The flood of grief would overwhelm her; dementia would soon settle in, and she would be in a nursing home for four years until her death at age 90.

I reread of the beautiful day, sunny and bright, the sky so blue, that she’s talking to my father every night, that my mother’s doing better than anyone ever expected… I reread her words of acceptance and carrying on, of her great love and prayers for me. I think about how these buoyed me through every day of my life…even now.

I fold the letter back into its old envelope. I finish my lesson for the women’s conference, on learning the unforced rhythms of grace.

I carry Grandma’s letter with me.

I carry on.

*******

with thanks to Two Writing Teachers for the Tuesday Slice of Life Story Challenge