Come back to examine this image after you read: In how many ways does it represent the information in this post?

The big question on Day Three of our Teacher Summer Writing Institute: How do I see myself as a teacher of writing—no matter my grade level or content area?

The day became a collage of images and symbolism.

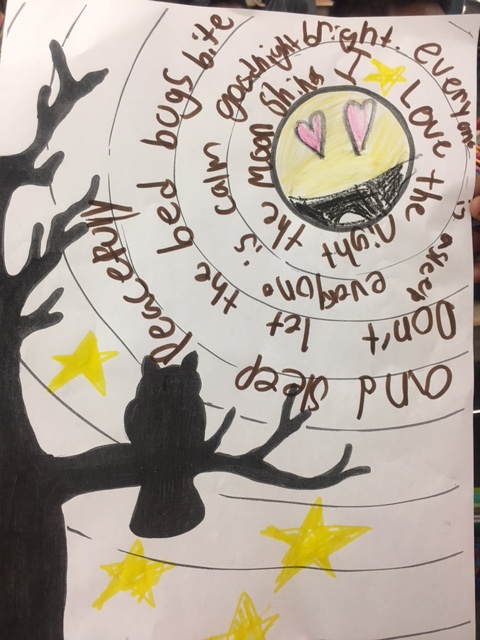

Teachers were tasked with using postcards and personal artifacts as metaphors for teaching writing. They used these ideas as springboards into poetry and a means of writing to inform.

Then came the birds.

It began with the fact that 2018 is the Year of the Bird. The National Audubon Society and National Geographic, among other organizations, made this designation to honor the centennial of the Migratory Treaty Act, the most powerful and important bird-protection law ever passed. My co-facilitator posed this question: How do birds inform us? Group answers: They indicate coming changes in the weather, or the quality of the air. Their migration patterns have changed because the climate has changed; the birds are getting confused. That’s a reflection of society and the world, don’t you think? This segued into an activity called “Everyone Has a Bird Story.” For just a couple of minutes, teachers were challenged with a quick write about a bird (everyone really DOES have a bird story of some kind). The teachers gathered in a circle afterward, each reading one line aloud from his or her story, to compose a group bird poem. The effect was funny, strange, and beautiful. The closing question: How might we use this activity to inform student writers? Answers: It’s a visual way to show students about organization and revision. Students can actually move around so that their poem makes more sense, or to attain better flow. You can use this activity to physically show students how to group like ideas. It’s an easy way to show students that writing is fun.

Just as the group broke for lunch, two birds—doves, to be exact—crashed into the windows of our meeting room. Generating both awe and alarm, they hovered, wings flapping, knocking against the glass as if seeking a way inside. A couple of us ran out to guide them away before the birds injured themselves.

Birds, ancient symbols of freedom and perspective, the human soul pursuing higher knowledge, the dove especially representative of peace, love, gentleness, harmony, balance, relationships, appearing at this gathering of teacher-writers as if invoked . . . so much to analyze there, metaphorically . . . .

Following lunch, the group spent time exploring abiding images. These are images that stay with us in our memories (and sometimes in our dreams); they usually have deeper meanings and significance than are obvious at first. One of mine, shared as an example: long, skinny, flesh-colored worms with triangular heads that my grandfather and I encountered when I was a child. He didn’t know what they were (land planarians, I’ve learned), we never saw them again, and neither of us could have guessed what they have the power to do. They just resurfaced in memory recently; I had to figure out why. Here’s the story of that experience, if you’d like to read it: First do no harm.

Participants were then invited to take virtual journeys in their minds to capture the specific sights, sounds, smells of their favorite places. Others went outdoors to capture the same (see Abiding images for my original experience with this). Whether the journey was real or virtual, everyone encountered something unexpected or fascinating —something so representative of writing itself. The point of collecting abiding images is the intensity of focus, the close examination and capturing of the smallest detail, which might be used later in writing vivid scenes and settings that are necessary in both fiction and nonfiction, as well as for metaphor in poetry. Writers communicate information to readers through images. Teachers must be able to test and try ideas and creative processes—this is called birdwalking—through things like abiding images to inform their teaching and to communicate information to students.

And to write.

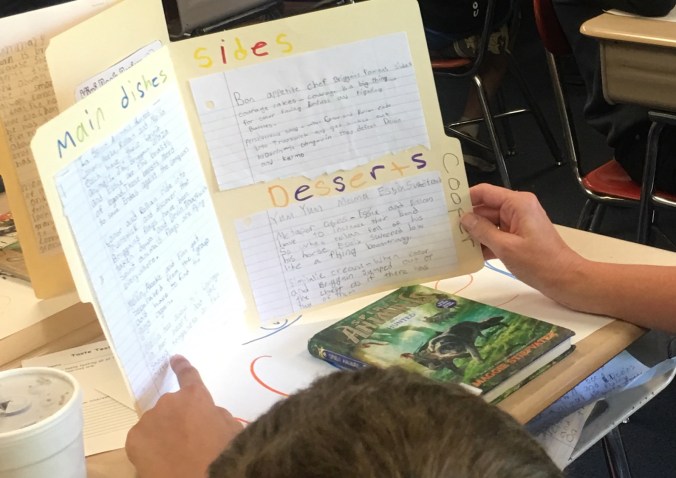

At this point teachers could rotate through any or all of three breakouts: Minilessons and content area writing, where they discussed ways to incorporate their new learning to grow student writers, or continuing to work on their own writing with the option of conferring with a facilitator, if desired.

As this vibrant day on writing to inform and “How do I see myself as a teacher of writing?” came to a close, my co-facilitators and I received the most welcome information from our fellow educators who span grades K-12 and all content areas, including ESL and AIG: These have been the most helpful sessions—I have learned so much about writing. There’s so much I want to try with my students! I am excited! How can I find more workshops like this? With most professional development, I am tired before lunch, and the afternoon is a long haul, but with these I go to lunch energized and can’t wait for the afternoon! The breakout sessions, where we choose to work on what we want to, are exactly what we need. Don’t change anything; just keep it coming!

That is like music—or shall I say birdsong?—to our ears.