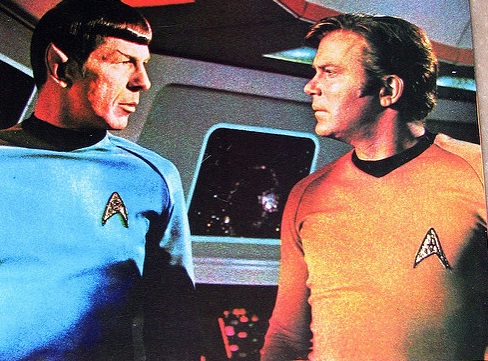

The following is a narrative/memoir written several times with students in grades 3-5. I wrote a bare-bones version in front of students, then revised to model the vast difference of “showing, not telling” by adding detail and dialogue. “I can see it all happening!” the kids always exclaim, as the narrative comes to life. Yesterday’s eclipse brought this piece back to mind – the fascination with space, the many hours I spent watching and playing Star Trek

when I was the age of these students. During the writing process, the kids ask countless questions. My favorite moment is when they realize what the story is really about.

I shake the device in my hand before I flip the lid and press the button to speak. “Do you read me, Spock?”

Nothing, not even static.

I pull the antenna out as far as it will go. I bang on the device a couple of times with my fist. I shout into it: “COME IN, SPOCK!”

My sister pokes her face from around the corner of our house. “This really ain’t logical!” she calls. She’s not even holding the device up to her mouth.

I sigh.

My sister is eight, I am ten, and we are tired of playing Star Trek. The batteries in the communicators we got for Christmas have quit working, and it’s no fun for Captain Kirk (me) and Mr. Spock (my sister) to keep yelling messages to each other across the yard, which has just one decent tree. There’s only so many pretend worlds we can explore when it all looks the same, with nowhere to hide from alien life forms.

My sister meets me at the street in front of the house. We leave our useless communicators behind in the grass and sit down on the curb as ourselves, not Kirk and Spock anymore.

“Let’s walk to the 7-Eleven and get a Slurpee,” says my sister. She likes the straws with the spoon on the end. She plays with them more than she drinks her Slurpee.

“I’m broke. I spent my last fifty cents on cinnamon Now-and-Laters and green apple bubble gum day before yesterday and it’s all gone already.” Our dad can’t stand green apple bubble gum. He says it stinks but I think it’s delicious, even though it turns my teeth and tongue green. “Do you have any money?”

“Nah, I thought you did,” says my sister, kicking at the grit beside the curb.

“Not anymore.” I wish I had some green apple gum right now. I stretch my legs, which are getting long, out into the road. If a car comes, which isn’t all that often in our neighborhood, my sister and I will pull our legs up to our chests until it goes by.

I look down at the edge of the curb where it meets the street, at the little loose rocks lying there. I see a stubby twig and pick it up to write my name in the dust when I notice tiny chunks of pale blue-green glass. I wonder where these came from. Someone must have thrown a Coke bottle out of a car and shattered it. I push the pieces around with the twig, inspecting them – they don’t look sharp. Time and weather, maybe, have smoothed away the roughest edges.

“What would you do if you had a million dollars?” asks my sister.

“I don’t know.” I pick up a bumpy chunk of the glass and roll it around in my hand; it sparkles in the sunlight. “Maybe I would have a horse and a big house. Maybe I would travel all over the world and be famous. What would you do?”

“I’d give some to poor people for their kids to have toys and bikes and then I would get me a bunch of dogs. What is that?”

I show her the bit of glass in my hand. I smile: “It’s an aquamarine. March’s birthstone. If you were born in March I would give it to you but since you weren’t, I will sell it for thousands of dollars.”

“Hey!” My sister is half amused and half irritated. “Look here—I got my own aquamarine!” She plucks up another bit from the curbside dust.

Suddenly we’re both on a wild treasure hunt, crawling along the curb so fast that we’re scraping our knees. We find bits of brown glass; we say it’s topaz. Green bits are emeralds, my birthstone. The clear ones are diamonds, of course. We can’t find any sapphires, my sister’s birthstone. We forget that this is trash, just pieces of bottles tossed out because someone else didn’t have the manners to put them in a trashcan. In no time we have amassed enough jewels for a princess, maybe two.

The sun shines warm on our backs and a couple of cars go by, slowing down, almost stopping, as they pass. Maybe the drivers are nervous about two girls crawling so close to the street or maybe they’re just trying to figure out what we are doing there in the dirt, but the quartz in the pavement winks at us, glinting like gold, and I know my sister and I are rich beyond compare. We are not afraid to pick our jewels out of the dirt, because dirt is just part of the world, and right now, we own the world.