To commemorate my last post of the month-long Slice of Life Story Challenge with the Two Writing Teachers community—this is my second year of completion—I write about “last times.”

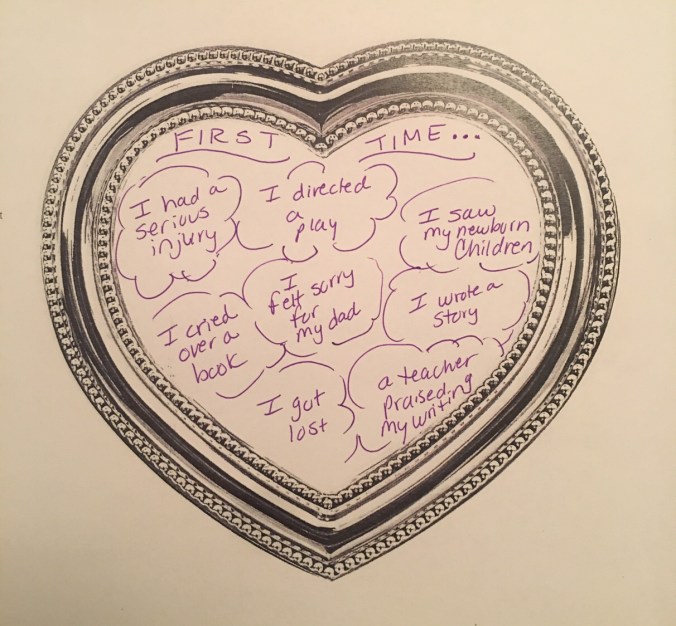

Yesterday I shared the “first time” heart map template from Georgia Heard’s Heart Maps: Helping Students Create and Craft Authentic Writing. I use these templates when I lead professional development for teachers in writing; it’s astonishing how often I hear teachers say, “I used to love writing but I don’t do it anymore.” More frequently, I hear: “I’m not good at teaching writing.”

The first step is simply to start writing.

The first and last time maps are excellent guides for this, and, furthermore, when teachers have taken these back to their classrooms, they tell me they’ve been amazed at what they learned about their students: “One of my boys wrote ‘the first time I rode a camel’. The class was so intrigued that he had to tell the story right then! We never would have known this if we hadn’t used the first times map.”

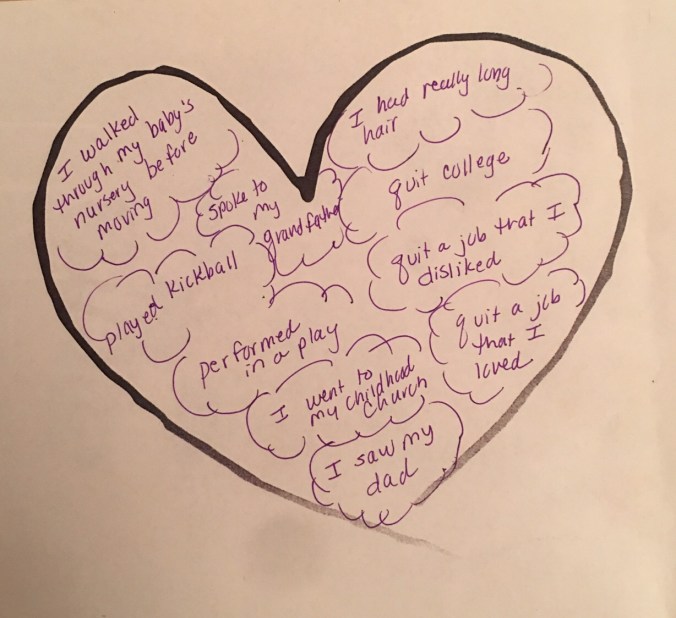

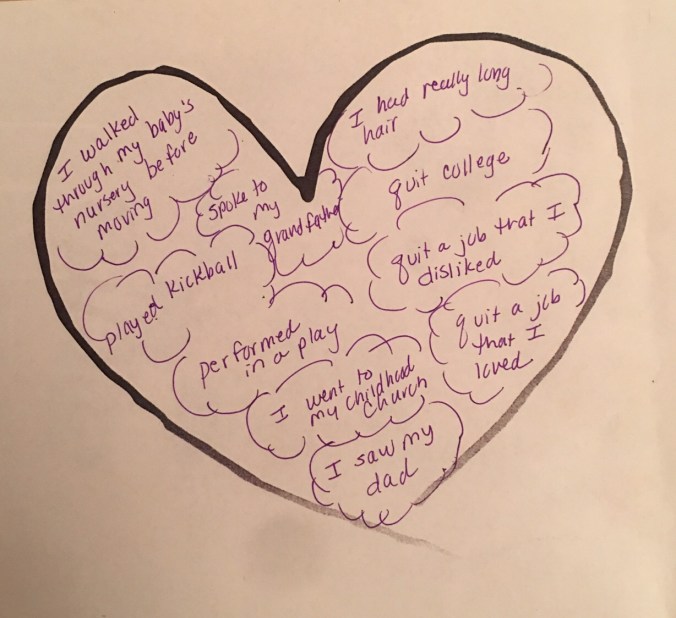

On to last times . . .

Here are mine, maybe to be spun out into full stories, one day:

The last time I walked through my baby’s nursery before moving. My older of two sons was born when my husband was in his first pastorate. The parsonage where we lived was a former sea captain’s house, built in 1915 (the year my grandmother was born), two blocks from the Chesapeake Bay. The congregation was mostly elderly; there hadn’t been a baby in the church, or the parsonage, for a long time. I was just twenty-two when my husband and I moved in, and I got to choose the wallpaper for the bedrooms. For the room that adjoined the master bedroom, I picked an ivory paper with little muted-red hearts between dusty blue stripes. A year later, I bought ivory crib sheets and bumper pads along with coordinating quilts and wall decor all adorned with these same little rustic hearts, teddy bears, and rocking horses. Our son was three when we left the Eastern Shore of Virginia to serve a church in North Carolina. I walked through the empty nursery last, where the only the little hearts remained on the walls; I stood there, running my fingers over them, and wept.

The last time I had really long hair. From kindergarten and first grade, when my hair was cut in an assortment of horrible shags, not to mention my cowlicks, I wanted long hair. By fifth grade, it was finally beginning to happen. In sixth and seventh grade, my hair reached down to my waist, was parted in the middle and as straight as a stick. In eighth grade I had a crush on a boy in my algebra class. He sat behind me. He’d speak to me occasionally, sometimes asking for help (which shows what dire straits he was in, to ask ME for help with algebra). I decided to cut my hair solely to get this guy’s attention . . .

The last time I played kickball. That was about a week ago! Due to a series of unfortunate events, there was a shortage of substitute teachers at my school on fourth grade’s quarterly collaborative planning day. I found myself taking a class to recess. It was a sunny, first true spring-like day, and the kids produced a kickball. “Mrs. Haley, will you pitch for us? Pleasepleasepleaseplease?” I haven’t played kickball since I was ten years old . . . but I was good at it, so . . . I took my place on the pitcher’s mound. My beginning teacher in kindergarten, walking past the game with her class on the way to the gym, stopped to gleefully take pictures.

The last time I quit a job I disliked. I’d had enough. I told the employers so and walked out. I never went back. Better things came along. Since then, when colleagues and friends have spoken of how much they detest their jobs, I’ve asked: What are you going to do about it? Life is too short to be spent doing something that makes you miserable every day.

The last time I performed in a play. I was in my second year of college. I planned to be a theater arts major, having performed in numerous high school productions, and I’d just auditioned and been accepted to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City. This really sounds like a story of beginnings, doesn’t it? To stay immersed until I left on this huge new venture, I performed in community theater. At the audition for the very next play, after receiving my letter of acceptance to the Academy, I walked in, saw the handsomest man I’d ever seen in my life . . . and got married that summer instead of going to acting school.

The last time I went to my childhood church. My husband and I attended the service honoring my retiring childhood pastor, who’d become mentor to my husband, the last of over fifty young men my pastor ordained into the ministry. The church building was large; I remembered how, as a child, I’d occasionally run upstairs—there were flights and flights of stairs, some of them not adjoining; I’d have to run across some entire floors to pick up other staircases—and I’d go as far as I could, up to a little door with a dark window. I tried the doorknob. It was locked. I wondered: What’s behind there? Can I go any higher? Is God on the other side, somewhere? Who keeps the key?

The last time I spoke to my grandfather. He was dying of lung cancer, at ninety-two. He stayed at home with hospice care and refused morphine. From his years around loud equipment in the shipyard, Granddaddy was notoriously hard of hearing. He never talked on the phone for this reason, but one day when I called to see how he was, he answered the phone. Grandma had stepped outside. I talked to him for just a few minutes, almost shouting into the phone so he could hear me. He understood every word. I said, I love you, Granddaddy. You’re safe in God’s hands. He said, emphatically: I love you, Honey, and there’s no better place to be.

The last time I saw my dad. It was the week of July 4th. I’d come home with my boys to stay a few days, as Daddy wanted to take us to the shipyard to see the fireworks. He was retiring at the beginning of October, after almost forty-one years as a security guard, so this would be the last time, the only time, we’d get to do this. There’s a lot to the story that I’m not up to telling, even now; maybe one day . . . so we went, my boys and I. As I sat there in the dark, watching the sky explode in lights over the vast, beautiful river of my childhood, sipping the ginger ale Daddy brought to share, I thought: Surely this is the beginning of better times. Daddy’s going to have more time to spend with us now. In my heart, I celebrated for him, that his working days were just about done, that soon he could take it easy and enjoy life . . . I could never have imagined it would be the last time I’d see him. In September, just three days before he was to retire, he died with a massive heart attack. In uniform, on his way to work.

Writing about last times can be so hard, so hard, so hard.

But not always . . . as my workshop participants tell me, there’s that last car payment, that last mortgage payment, causes for celebration, indeed. Maybe even a step toward health, as in the last time someone smoked a cigarette.

So I close my thirty-one day writing streak, celebrating that I made it to the last post, celebrating my fellow Slicers who did the same, who wrote alongside me, who walked a part of the journey with me every day. Here’s to writing, friends. Here’s to sharing each other’s stories as long as we can, though perhaps not daily until next March.

Thank you all.

Here’s to your first and last times, to what’s in your heart, and to life.

Keep trusting.