A little slice of memoir

*******

I was five when my dad bought the house where I grew up.

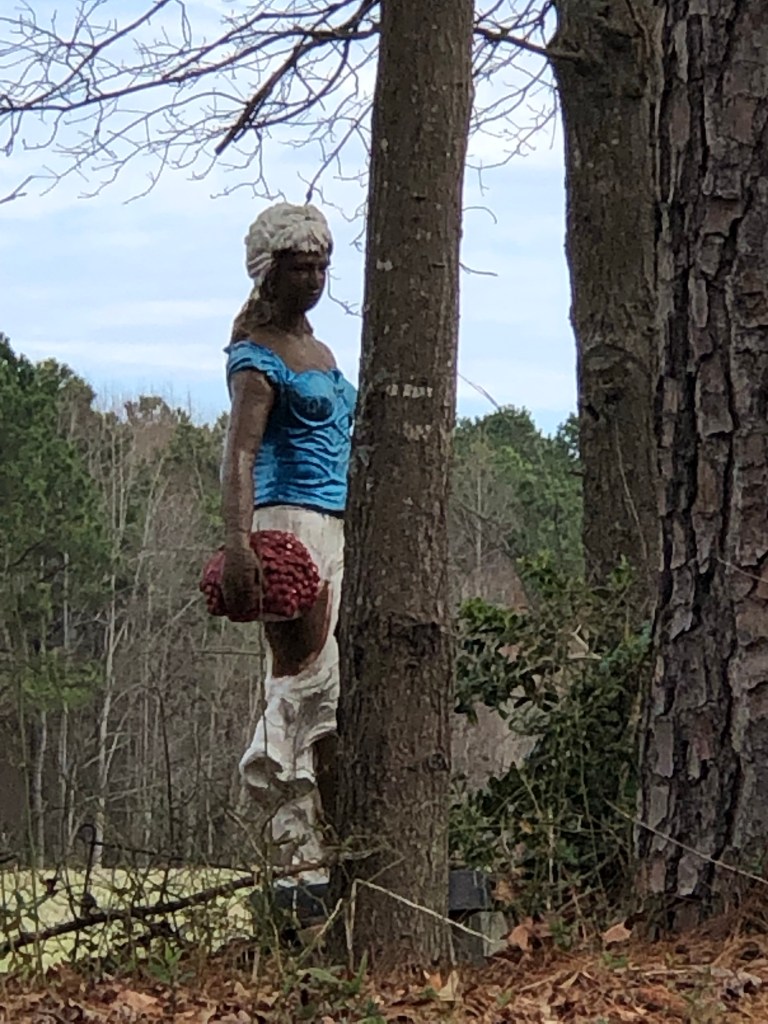

There were good things about the house. A Big Bathroom and a Little Bathroom. Having two seemed luxurious to me, a child accustomed to apartments. Cloud-like swirls on the ceiling that my mother said were made by twisting a broom in the plaster while it was wet. A huge picture window in the living room, through which I could see a very tall tree behind the neighbors’ house. To me, the tiptop of the trunk appeared to be a lady sitting and gazing across the earth like some kind of woodland princess. Day in and day out, she sat there atop of her tall tree-throne, a regal silhouette, never moving.

There were things I didn’t like about the house. The red switch plate on the utility room wall that my father said to never ever touch. I believed that if anyone touched this switch, the furnace would explode and blow us all to smithereens. Even after I outgrew my terror, I steered well clear of that red plate. I didn’t like the thick gray accordion doors on the bedroom and hall closets. Bulky, cumbersome, and stiff, they didn’t really fold. They came off their tracks easily. These hateful doors eventually disappeared; one by one, they were discarded. Our closets were just open places.

The linen closet stood directly across from my bedroom door in the narrow hall leading to the Big Bathroom.

It wasn’t a true closet, just a recessed place with wooden shelves. I don’t remember an accordion door ever being there.

What I do remember is that one of those linen closet shelves had a terrible gash along its edge.

It looked like a raw wound that might start oozing at any moment. A gaping slit. When I pored over pictures of how to do an appendectomy in my parents’ set of medical encyclopedias (and why did we have these—? An exceptionally persuasive door-to-door salesman—?) the pulled-back human flesh and tissue made me think of the wound in the linen closet shelf.

This shiny-pink raw place bothered me. It was ugly. Almost…embarrassing. Something that shouldn’t be seen, shouldn’t be exposed…why had the builders done this? Couldn’t they have turned the shelf around so the wound wouldn’t show? It was an affront to me as a child, before I knew what taking affront meant.

I know now that the flaw is a bark-encased scar. The shelf came from a tree (maple?) that was injured, somehow. Maybe by a cut or fire. An online search produces this AI-generated explanation:

The tree’s cambium layer, which is responsible for producing new bark and wood, starts to grow new cells around the wound, forming a protective layer of tissue called callus.

As the tree continues to grow, the callus tissue can expand and eventually cover the original wound, creating a scar that is encased within the new bark.

In short: The scar is evidence that the tree worked to prevent inner decay and heal itself after being wounded, and that it went on living for a good while before it ended up as the shelf holding our towels and washcloths beside the Big Bathroom.

I never touched that raw-looking wound in the wood. I averted my eyes from it, even hated it for existing.

Now, when I return in my mind to the rooms and halls of my childhood home, they are always empty, and that old scar in the shelf is the thing I want most to see.

How strange.

Maybe I am drawn to it out of kinship. I do not know the story of the tree’s life, only that this remnant is testimony to its suffering and ability to overcome. I could liken the scar to the ways adults damage children, having been damaged as children. I could see it as a symbol for my mother, whose early wounds festered long, the extent of which would eventually be revealed in addiction.

That’s the real red switch, for it blew us all apart.

Maybe I just want to place my fingers on the old raw place at last, tenderly, in benediction. I would say that I understand now about layers of callus tissue expanding, covering, and absorbing the deepest of cuts over a long, long time…it is always there, but it hurts no more, and I am no longer ashamed to see it or to let it be seen.

In the shelf or in myself.

Image by Wolfgang Eckert from Pixabay

*******

with thanks to Two Writing Teachers for the March Slice of Life Story Challenge