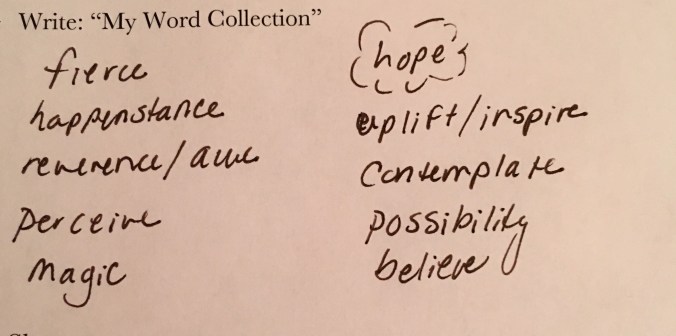

Drema Gaye Spencer. Her first name means “reverie,” or dream. Her middle name, “merry, lighthearted.” Her surname is Old English for “guardian,” “object of awe,” “dispenser of provisions.”

She stands on the precipice between childhood and womanhood, facing the camera directly, her hooded eyes steady and confident. She does not know it yet, but she will be like the mountains framing her background, where she and her seven siblings loved to run, calling to each other across the distance, teasing, playing jokes, laughing with wild abandon at their own mischievous humor. As intense pressure, heat, and time formed the ancient Appalachian coalfields, so the course of her life would forge an internal fuel, the deep, burning drive to keep going under the weight of crushing adversity.

It’s the early 1940s. World War II is in full swing; her three brothers have enlisted in the Navy. The family has survived the Great Depression in the place it struck the hardest, where the economy has always been precarious. When she arrived with the January snows of 1926, her coal miner father hadn’t had steady work in a year due to frequent safety shutdowns; the West Virginia Office of Miner’s Health Safety and Training references nearly 700 fatalities for 1925.

She’s just a teenager with a head full of dreams for the future.

Maybe she could teach English literature and composition—What fun that would be! Maybe I’ll even visit England one day.

Innately musical, singing harmony with her sisters in church, she also harbors aspirations for the stage. She knows she has true dramatic and comic talent, which, along with her natural beauty, lands her roles in high school plays. Her blue eyes sparkle: Well, I AM a good actress. Very good. Eventually, of course, I’ll get married and have children. I do want children . . . Sometimes she can almost see their little faces, these someday-children. I hope one’s a boy with brown eyes.

So she looks at the camera and smiles, the mountain beneath her feet, her childhood behind her and her whole future lying ahead.

But I, being poor, have only my dreams; I have spread my dreams under your feet; Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

-William Butler Yeats

The reality is that just a few years after this photo was made, she married a man who would be killed in a mining accident, leaving her with a toddler and a baby at twenty-three.

Several years afterward, she married a widower, an Army man with two older children. Eventually they had a boy and a girl together.

Her boy with brown eyes.

When her husband completed tours of duty in Korea and Vietnam, she cared for the six children by herself.

When the brown-eyed boy was four, he developed acute bronchitis, necessitating an emergency tracheotomy. His temperature spiked to 107 after surgery. The nurses packed the child in ice. The hospital doctors told her that her little son might not make it. She sent for his father, away at Army summer camp; a police escort was dispatched to meet him at the airport. As the boy drifted in and out of consciousness, she sat by his oxygen tent, praying, weeping.

The boy survived.

She wrote him a letter on the inside back cover of a book of Bible stories.

4:00 a.m. In hospital.

Dearest . . .

When you are well and safe at home again, I’ll read you this little note I’ve written to you during the hours I sat by your bed and watched you sleep so soundly . . . Mommy and Daddy have been so scared . . . We love you so much, our little son . . . Little angels have been all around your bed since you have been sick and Jesus sent them to watch over you and keep you . . . soon all the suffering and fright you have had will pass from your little mind but Mommy will always remember and thank God for giving you back to me.

Your Mother

She could never speak of the ordeal without tears.

Staggering losses were yet to come.

When the brown-eyed boy was twelve and his sister nine, and all the others grown and on their own, her Army man died suddenly, instantly, with a heart attack.

Widowed twice—each time with a boy and girl at home to care for.

Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.

-I Corinthians 13:7

When her sobbing son asked, “Who’s going to take care of us now?” she wrapped him in her arms.

“God will. And I will.”

And she did.

Survival ran in her veins like coal beds through the Appalachians. She dug deep within herself, tapping into the hardy DNA passed down by her ancestors, into the wellspring of her faith, into the fierce love for her children, and carried on. When her son was consumed with fear of something happening to her, she said:

“I have prayed and prayed that nothing will happen to me until you’re grown. And I am convinced that God will allow it.”

For the next ten years, she poured herself into her children and her home.

Still she laughed. Still she sang. She called her brothers and sisters, who still teased each other with jokes old and new. She gardened. She arranged flowers. She organized a women’s political group, taught Sunday School, went to her son’s basketball games all through high school.

She managed, and managed well.

When her son said he found the girl he wanted to marry, she gave him her blessing and the diamond engagement ring that his father, the Army man, had given her.

The brown-eyed boy—now the man—gave the ring to me on my twentieth birthday, long, long ago.

For the boy who lived (apologies, J.K. Rowling) is my husband; the woman in the photograph is my mother-in-law.

When I came to know her, I first admired her elegant, impeccably-kept house, which she was forever redecorating. And the food, the food, oh, the food! Her table always looked like something from Southern Living, down to the coordinating linen napkins and rings. Her iced tea was always blissfully sweet and there must always, always be lemon slices with it. I came to appreciate her ever-present wit, her spunky humor, her fashionable attire. Being well-put together was a priority to her. I browsed her bookcases on every visit, knowing she’d have a new bestseller for me to devour. I was instantly at home in her home.

When she was sixty years old, a third man proposed to her. She hesitated. “I’ve buried two husbands. I don’t want to bury a third.”

But he was a good man; she took a chance on him. For the next three decades, they celebrated the coming of grandchildren and the first great-grandchildren.

Three years ago, she was widowed for the third time.

There were no children at home to care for now.

She was, for the first time in her nine decades, alone.

With housekeeping being too much for her, it was time to go to the home of one of the children or to assisted living.

And her genes, or her Appalachian roots, or the rising dementia—or all three—kicked into overdrive.

She would not go.

The house had become her whole identity. It was where she’d provided for the last of her children. It symbolized her strength, her ability to survive. This was her mountain; she would not be moved. She dug in her heels. Deep.

Until the stroke.

After surgery, when her family was allowed to see her in intensive care, she greeted us with a smile. “I can’t believe I’ve had a stroke! Can you believe it?” she said, as if she were sitting in the den at home, making everyday conversation, even as the nurses watched her monitors. Blue eyes sparkling as bright as ever, she reached out her warm hand to grasp mine. “Hey, you’ve got a birthday coming up. We’ll have to celebrate.”

I held her hand, marveling.

She rebounded for a short while, working hard at her rehab, thinking she could go back home. She couldn’t. She went into a nursing home instead, for, as the weeks wore on, her strength waned.

So did her mind.

The one thing that waxed bright and hot was her fighting spirit. She grew more determined to go home, even as she grew weaker, less hungry, more and more tired.

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

-Dylan Thomas

She raged. She burned within like a coal seam fire, until her energy was spent at last.

Lying in her nursing home bed, she stood on the mountains again, seeing her brothers and sisters in the distance. She called their names over and over—only the ones who’d already died. She carried on conversations with them.

“I can’t go on up,” she told these siblings that the rest of us couldn’t see. “Not just yet.”

She knew us, called us by name when we last gathered with her, at Thanksgiving. Within the hour, she couldn’t recall who we were, or why we were there.

Still she sang.

There is coming a day, when no heartaches shall come

No more clouds in the sky

No more tears to dim the eye

All is peace forevermore

On that happy golden shore

What a day, glorious day, that will be . . . .

“My throat hurts,” she said. “I can’t sing any more.”

“It’s okay,” said her children. “You don’t have to.”

They moistened her lips and mouth with water.

And still she sang.

If we never meet again this side of heaven

I will meet you on that beautiful shore.

And then she sang no more.

She rested a while, then, with her eyes closed, turned her face toward her brown-eyed son, my husband.

“Where do you live?” she asked.

“North Carolina,” he replied, smiling through his tears.

“Oh, my son lives there,” she said.

“Yes. I am your son.”

She opened her eyes the tiniest slit. “Well. You’re all grown up.”

It was the last thing she said to him.

I have prayed and prayed that nothing will happen to me until you’re grown. And I am convinced that God will allow it.

A few days later, my husband, his younger sister, and my son, the youngest grandchild, sat by her bedside all morning, watching her labored breaths. Finally they told her, “We’re going to go eat lunch, Mom, but we’ll be right back.”

The minute they finished eating, the nurses called. “The time is near.”

They came. They took her hands.

She took two labored breaths, and was gone.

She’d waited for them to have their lunch. To the very last, making sure her children had what they needed.

She never taught school.

She was never an actress of renown.

She never made it to England.

She lived one of the most extraordinary lives I’ve ever known.

The diamond on my finger shines as bright as it ever did; I can only hope that a portion of her strength, her courage, her wisdom has passed on to me along with it.

I look at her teenage photo, contemplating all that she will endure.

All that she did endure, and need endure no more.

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see’st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

In me thou see’st the glowing of such fire

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the death-bed whereon it must expire,

Consum’d with that which it was nourish’d by.

This thou perceiv’st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

-Shakespeare, Sonnet 73

She loved as deep, as far, as long as she possibly could, with every ounce of her being. That is what I will remember most, her fierce, fierce love. It burns on, and on, and on, bright and warm, forevermore.