Stained-glass birds. Jesse Radonski. CC BY

Elizabeth, Elspeth, Betsy, and Bess

They all went together to seek a bird’s nest.

They found a bird’s nest with five eggs in,

They all took one and left four in.

—Mother Goose

It’s the summer of birds.

They became a recurring motif in my summer writing workshop. 2018 is actually The Year of the Bird, marking the 100th anniversary of major bird protection laws. I’ve discovered that I’ve written enough bird stories to give them their own category for this blog. I am reading a stunning, lyrical book recently recommended to me, When Women Were Birds: Fifty-Four Variations on Voice. I recalled the friendly little parrot I saw at a store a while back, and thought—for maybe seven seconds—about how nice it would be to have another pet bird.

And so they came. As if summoned.

House finches, they are. A pair built a nest in my lantern porch light fixture. I would not let my family turn on that light at night for fear of burning the birds. A brood hatched, grew quickly, and was gone; here’s a fledgling tarrying behind on the last day:

Once the nest was empty, our younger son, Cadillac Man, removed it and my husband had the house power washed (a thing well past due).

A day later, I heard a commotion on the front porch.

Birds. Very loud ones.

The front window blinds were up; I could see a male finch, a soft dusting of red on his breast, hopping to and fro along the white railing like an Olympic gymnast on a balance beam (forgive the mixing of genders here but that is what he looked like). He paused to stare right back at me. A speckled brown female flew to him, then instantly away again. Two or three more finches skittered nearby. The collective chatter seemed highly agitated—consternation is the word that came to mind.

It’s the nest, I thought. They’ve come back and it’s gone.

They had to be the same mother and father. I wondered if the others were part of their newly-grown brood. Or a support group. Some sort of council? They seemed to be consulting over the vanished nest. Maybe problem-solving? Collaborating? Making decisions?

For two days, the lively bird debate continued.

Then it died down.

And a piece of pine straw appeared in the bottom of the lantern.

From the window I saw both male and female bringing more pieces, saw the male drop his on the porch floor, fly down to retrieve it, and hover like a hummingbird to work it into place.

My older son, The Historian, passing through the hallway, stopped beside me to watch: “It’s amazing how they know to do this.”

“What’s going on?” his father called from the living room.

“The birds are building another nest in the porch light,” I told him.

“Oh, no they’re not,” he said. “We just had the house washed. The porch was disgusting.”

He went to the kitchen, rummaged in a drawer. He went to the porch, pulled out the three pieces of pine straw.

And put aluminum foil in the lantern:

It sent the finches into a frenzy. For another day, the loud bird-chatter resumed. I found a bit of foil on the porch floor; had one of them tried to tug the stuff loose?

And I worried about the birds cutting themselves on the aluminum, about time elapsing when they clearly needed their nest. The female must be getting ready to lay more eggs, or why all this fuss?

What would they do?

The next day when I opened the front door to go get the mail, I heard a rush of wings and I knew.

The wreath on the door.

Sure enough, on the top of the wreath lay a few long grasses.

I chose to keep this a secret for several days, until:

“All right, you guys,” I announced to my menfolk, “we now have a nest on our wreath with an egg in it. No opening the front door until these birds are gone.”

I may have also mentioned, nonchalantly, that it is illegal in the United States to remove a nest containing eggs.

And then I worried even more: Is the wreath secure enough? How many more eggs will there be? Will they—will the babies—be safe?

The nest made me want to cry. At the perfection of it, at the dried dandelions laced through it like deliberate decoration, an artist’s touch. I wanted to cry at the determination of these birds to live on my porch, how they persevered in rebuilding their home from scratch. They do not know that they built on the door of my home as well as on my heart, where there’s an especially tender spot these days for little creatures and their well-being. I still mourn a small dog, grown old and frail, that I could not save. A rawness in my soul that has yet to grow new skin.

While these birds do not really need me, they spark a sense of ownership and protection. They’re in my realm now, in my sphere of influence.

All I can give them is sanctuary.

I remember how, when I was a child riding in the backseat of a car watching the cityscape give way to fields and forests, a little green sign appeared:

BIRD SANCTUARY

I puzzled over this: Where’s the bird church?

It took some time to understand that birds can’t be hunted here, that sanctuary means safe place.

A place to be, grow, flourish, and fly. Something every living thing needs.

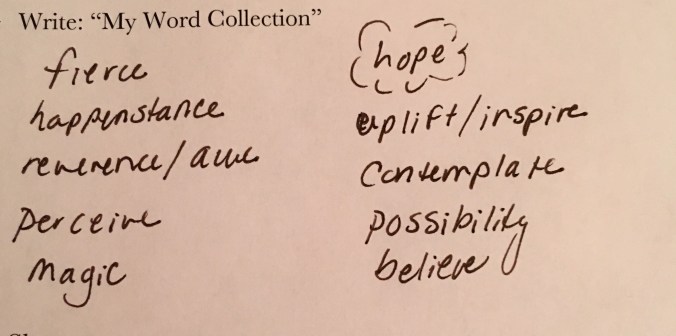

Sanctuary was the word I chose to describe the writing workshop just a month ago. The workshop that had the bird motif running through it. A safe place to think, explore, write, share.

So now, every morning, when the sun is new, when shadows are sharp on the ground, while the dew is still sparkling on the grass, I walk from the garage door to visit the sanctuary. Mama Finch sees me coming as soon as I round the corner; she flies out of the nest, bobbing through the air without a sound. There’s a reverent silence, a holy hush, in sanctuaries, you know. She waits on the rooftop while I quickly admire her handiwork. I go before she’s troubled. I’ve learned from these visits that she lays her eggs between 7:00 and 8:00 a.m.

As soon as my husband and I returned from a trip to the beach, he asked: “Have you checked on your eggs?”

“Yes,” I said, smiling at his words. My eggs.

I have four.

*******

Stay tuned for the hatching announcement.

While writing this post I could not help thinking how “sanctuary” applies to teaching and instructional coaching. As with the house finches—which are symbolic of joy, happiness, optimism, variety, diversity, high energy, creativity, celebration, honoring resources, and enjoying the journey—a safe place to be, grow, flourish, and fly comes through concentrated, collaborative effort. Right now my finches are singing. A song, perhaps, that all of humanity still needs to hear.