The title of this post might have you wondering if it’s about a mnemonic aid or a literary device (also known as “Rule of Three”). Perhaps you envisioned triangles — the strongest geometrical shape in the context of civil engineering and architecture — or the algebraic exponent, as in “to the third power,” i.e., cubed. Or maybe even the Trinity.

But today I am pondering the power of three as it relates to the human brain, words, and reading.

As inspired by a little person who’s been staying with me each day for a few weeks this summer.

She is three years old.

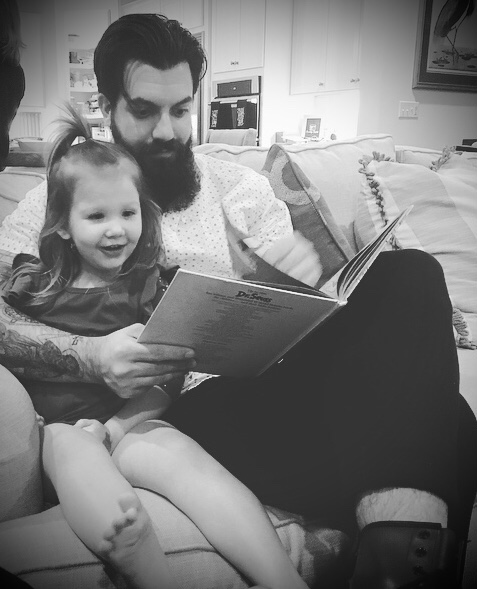

Her mom and my son, who’s a newcomer in their lives, read to her each night.

So each day, as she settles for a nap, I read to her from an assortment of books I keep in baskets here at home. Some of these I bought just for her. Most are from my personal collection at school, a few are old favorites of my sons, and a couple I salvaged from stacks discarded by teacher colleagues who considered them too outdated (a worthy topic for a later post . . .).

And each day, of her own volition, my new little girl picks the same three books: Curious George Goes to the Hospital, A Bad Case of Stripes, and Green Eggs and Ham.

That is the exact order in which she insists they be read each day.

I think of myriad things while reading this rather motley selection to my rapt little listener. Two of the books have been in print for over half a century. Their illustrations are simple. The the third has elaborate illustrations and a story that might be deemed too strange or “above” a preschooler’s interest and capability to understand. While she examines various books throughout the day, poring over pictures on many pages, it’s always these three books she clutches in her arms as she climbs into bed for nap. I am reminded, yet again, of the inestimable power of reading aloud, rereading, and familiarity. And of choice.

I also think about the impact of language on a child’s developing brain. It just so happens that a book in the stack of my own summer reading is Thirty Million Words: Building a Child’s Brain, in which the author (cochlear implant surgeon Dana Suskind) writes: “By the end of age three, the human brain, including its one hundred billion neurons, has completed about 85 percent of its physical growth, a significant part of the foundation for all thinking and learning. The development of that brain, science shows us, is absolutely related to the language development of the young child. This does not mean that the brain stops developing after three years, but it does emphasize that those years are critical” — because the neural pathways for language are being created only in that window. As a literacy educator, I mull the importance of early phonemic awareness in conjunction with Suskind’s words: “It takes more than the ability to hear sounds for language to develop; it is learning that the sounds have meaning that is critical. And for that a child must live in a world rich with words and words and words.” (Suskind later emphasizes the quality of language in addition to the number of words spoken, the power of affirmations on a growing child’s development. And her first line of her first chapter is “Parent talk is probably the most valuable resource in our world.”)

All of this swirls in my own brain as I reread the same three books every day to this three-year-old entrusted to me, as we converse about her observations and questions:

“What is a tube?” she asks, during the fifth (sixth?) reading of Curious George’s hospital visit. “Like a hose in the garden, only a lot smaller so it can go down George’s throat. Very small,” I say. “Tiny,” she declares with authority, and we go on with our sixth (seventh?) reading of this book.

“What is broke?” — when, in A Bad Case of Stripes, Camilla “broke out in stars.” This is a bit harder to define. “Hmmm. Has your skin ever had a rash, or a lot of tiny spots on it?” She nods hesitantly, and I say, “Then your skin broke out, meaning it suddenly got spots or little bumps on it for a while.” I can tell by her solemn expression that this information is being processed. A minute later: “What is sob?” When I say it means to cry a lot, not just a little, the light of understanding flickers instantly in her wide blue eyes.

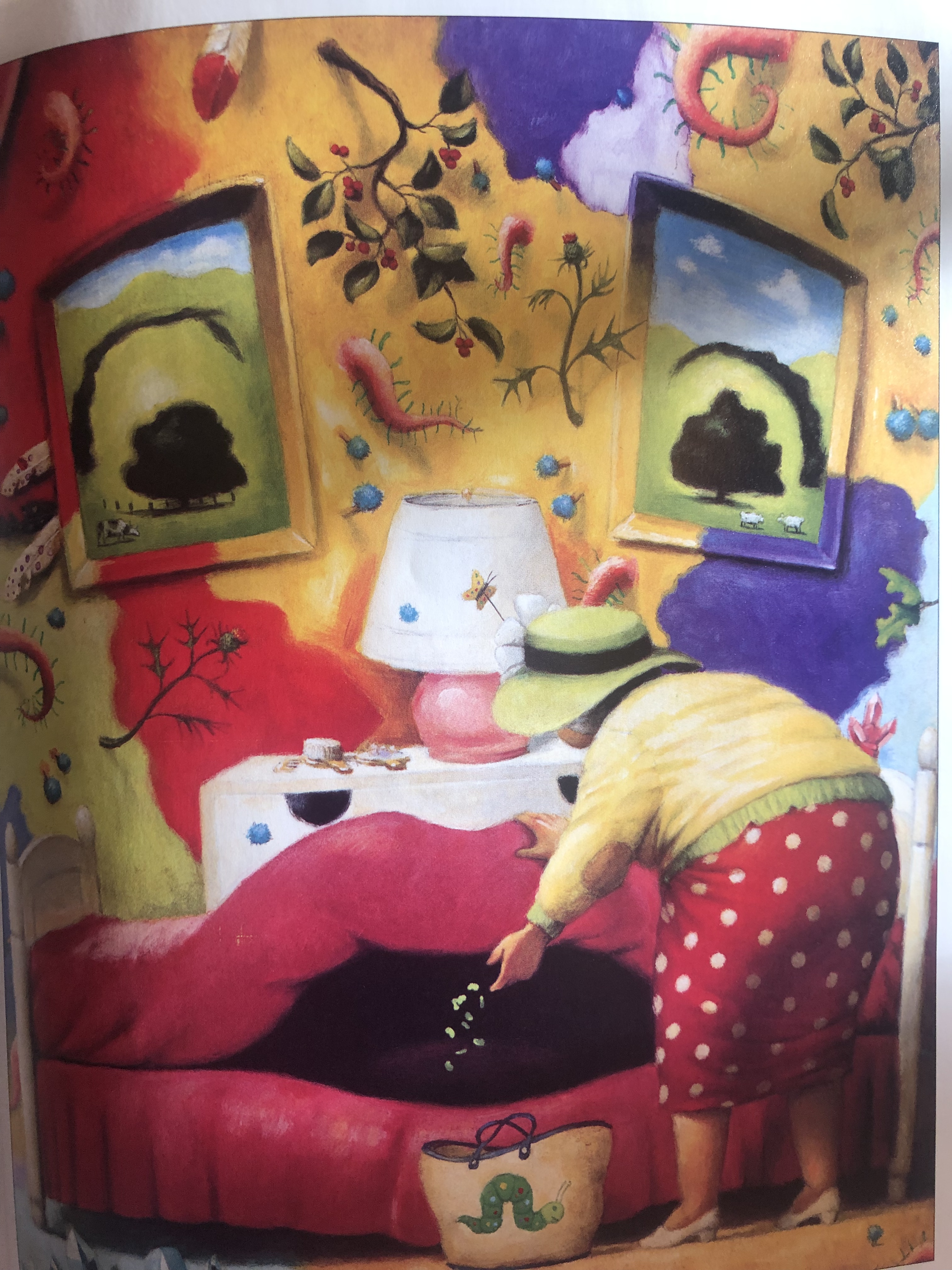

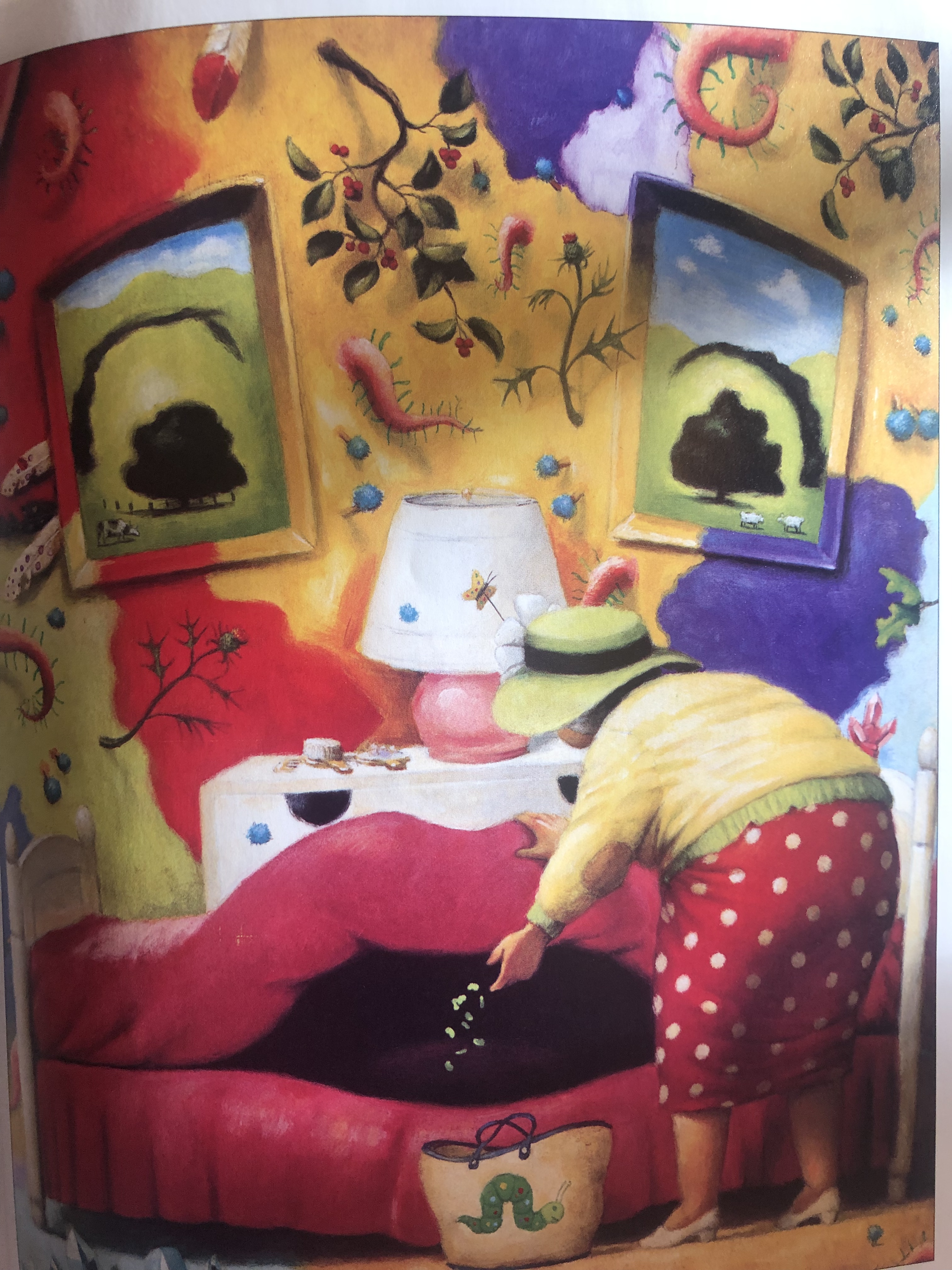

I continue this umpteenth reading of Stripes to the page where the old woman who will cure Camilla arrives, just after the visit from the Environmental Therapist who told her to “breathe deeply and become one” with her room. Camilla became one with her room, all right; she melted into the walls where two pictures became her eyes, a dresser morphed into her nose, and her bed turned into her mouth. Totally abstract. Transcendental. Out there. I read in my best kind-old-woman voice: “What we have here is a bad case of stripes. One of the worst I’ve ever seen!”

My listener giggles. “It’s not a bad case of stripes. It’s a bed case of stripes.”

A pun so profound that I am at a loss for words.

She’s three.

I make a mental note to tell her mom, who’s clearly laid a magnificent foundation long before now.

This perceptive child notices the letters down the side of the Stripes front cover. She attempts to sound them out, and I let her try for a minute before telling her the words are “Scholastic Bookshelf.” She points to the square between the words and asks, “Why is this one blank?” I am excited: Print concepts! Teachable moments! “That’s a space. They come between words. See, this is a word. Then a space; this is another word . . .” She picks it right up: “And this is a word, this is a word . . .”

Truth is, all moments are teachable moments.

Even though her eyes are growing heavy, she chimes in with the rhyming words in Green Eggs and Ham. In fact, she takes over reciting portions without my help now, mimicking my expression and cadence, on all the right pages . . .

I leave her to her nap. I wonder if her dreams will be filled with monkeys, phantasmagorical color patterns, rhythms, rhymes, words, words, words. My husband is compelled to check on her after awhile. He whispers his report: “She’s sound asleep.” Obliviously recharging her power of three for the remainder of the day, and for a future brimming with potential.

To the power of infinity and beyond, one might say.

And I believe it.