Way back on Day 10 of this current Slice of Life Story Challenge, I had a lot of fun playing around with a prompt asking what the first line of my autobiography would be. I really prefer the idea of memoir…my definition: Mining one’s memories for the stories that matter most, digging in the storied strata of one’s past.

I came up with this “opening line” for it:

My father named me for his mother, and that was the beginning of everything.

Truth.

From the moment I entered this world, my grandmother and I were bound together by blood, love, and namesakery. Long after she’s left it, our bond remains unbreakable.

Were I ever to write an extended memoir, her stories would be layered throughout. I am part of them; they are part of me.

She would say, You were named for me like I was named for my Papa. I loved him so. He was very religious, sang in the choir every Sunday. He had a beautiful bass voice…he used to keep bees when I was young and I’d help him get the honey.

She was sixteen in March of 1932 when her Papa, Francis, died by suicide. On his sixtieth birthday. I don’t know the whole story but what little I do know, I shall keep for now. Grandma told me they brought him home in a wooden casket lined with black oilcloth and that she sat up with him all night before the burial.

The point is that my grandmother’s stories made me hungry to know as much as I could about her childhood, daily life long ago, how people endured such hard times. Many didn’t. The old cemeteries tell stories of their own.

I asked her about the 1919 influenza epidemic: I don’t remember it. I was little. I do remember people talking about “hemorrhagic fever” and Mama saying she made big pots of soup for the neighbors who were sick. Papa carried it to them and left it on their porches. He wouldn’t go in because he didn’t want to bring the sickness home.

I asked her about meeting my grandfather: Oh, we always knew each other. He’s nine years older than I am and he and Mama used to pick cotton together…

Granddaddy would say: We’d all see who could pick the most cotton and it was always Lula [Grandma’s mother] or me. That was before the boll weevil came along and people started planting tobacco.

Grandma said: When tobacco came along, I was a looper…you had to be careful. That juice was sticky and would stain your clothes; it was hard to get out…using a wringer washing machine or washboard, I might add.

The setting of all this is a tiny community called Campbell’s Creek, established around 1700, way down east in the far reaches of Beaufort County, North Carolina. It’s part of Aurora although the actual town is five miles away. Most of the town is now in serious disrepair and the place is so remote that when I happen to encounter people who’ve been there, they typically say something like “I thought I was going to the end of the world.”

It is one of the places I love best on this Earth. The beginning of everything…Aurora is Latin for “dawn,” you know.

My grandparents, Columbus St. Patrick and Ruby Frances, were born here in 1906 and 1915, respectively. They married during the Great Depression. Their first home was a tenant house; their first child, my father, was born there. Granddaddy was a sharecropper. He plowed fields with mules. He was skilled with farm tools that people seldom use now, like an adze. This would give him a unique advantage when he “couldn’t make a go” of farming and went to Virginia to find a job as a shipwright, just as war broke out and ship production went into overdrive. When the war was over, he tried his hand at a number of things, but he had two more children to provide for; he went back to the shipyard until he retired.

All of his life, Granddaddy was a farmer at heart: I can remember when we ordered chickens by mail and they’d be delivered in cages by horse and buggy. I was three or four when I saw my first automobile…

That would have been around 1910. A Model T.

Time was, he’d say, in his country dialect bearing faint traces of Elizabethan English, that the whole family could go off for a week to visit somebody and you didn’t have to lock your house or barns because nobody would bother them. People looked out for each other. There won’t no nursing homes. When somebody was sick we all took turns helping out.

Grandma said: I was sitting with a friend’s mother. She’d been sick awhile and we all knew her time was near. She hadn’t spoken a word in days, hadn’t moved or responded to anyone. She was just lying there in the bed when all of a sudden she sat up and opened her eyes. She started laughing: “Can you hear them? Can you hear them?” Her face just glowed...it had to be angels. A little while after, she was gone.

I grew up on these stories and so many more.

My summers were spent learning things that I wasn’t even aware I was learning, things that will drive my interests for the remainder of my days: story, history, culture, nature.

Faith.

And science.

I’ve written much about the little dirt road that ran past Granddaddy and Grandma’s house. It’s one of my life’s greatest metaphors. I can recall, in the 1970s, when it was covered with gravelly “rejects” from phosphate mining, Aurora’s biggest industry since 1964. Granddaddy and Grandma were so excited for their grandchildren to come digging in the road to find sharks’ teeth—some were quite large — coral skeleton, and various fossilized bones of sea creatures. Someone of official status must have soon realized the value of these rejects and they weren’t scattered on the old dirt road anymore. Instead, they were taken to a newly-created fossil museum in town. Today, children from all over come to dig for fossils they can keep, and they can learn about the history in the little museum. There’s even an annual fossil festival at the end of May; last year I went for the first time with my seven-year-old granddaughter.

This excerpt is from an article in the April 2023 edition of the magazine Our State: Celebrating North Carolina:

Beneath our state’s soil and waves is a lost world waiting to be discovered—a geologic trove we claim as our own…about 50 years ago, coral specimens were found in drilling samples near present-day Aurora. They were sent to the Smithsonian Institution, whose scientists soon visited—and identified the area as one that proclaims the most prolific fossil record of the Miocene (2.3 million to 5.3 million years ago) and Pliocene (5.3 to 2.6 million years ago) marine life on the Atlantic coast.

About fifty years ago… I’d have been a child playing in the gravel on the old dirt road, collecting shark’s teeth, unware of the true treasures of my life.

The Aurora Fossil Museum, writes the author, “continues to keep the past alive.”

It’s analogous to to me: Scientists finding bits of ancient creatures, trying to piece them together to understand stories of this “lost world,” and how I hold to bits of story from this same place, the lost world of my grandparents.

Generations rise and fall…layer upon layer of story strata settling in their wake.

I am a remnant of their world. From early childhood Grandma infused me with story, unknowingly turning me into amateur oral history exacavator, archivist, curator…the stories still live in me.

My father named me for his mother, and that was the beginning of everything.

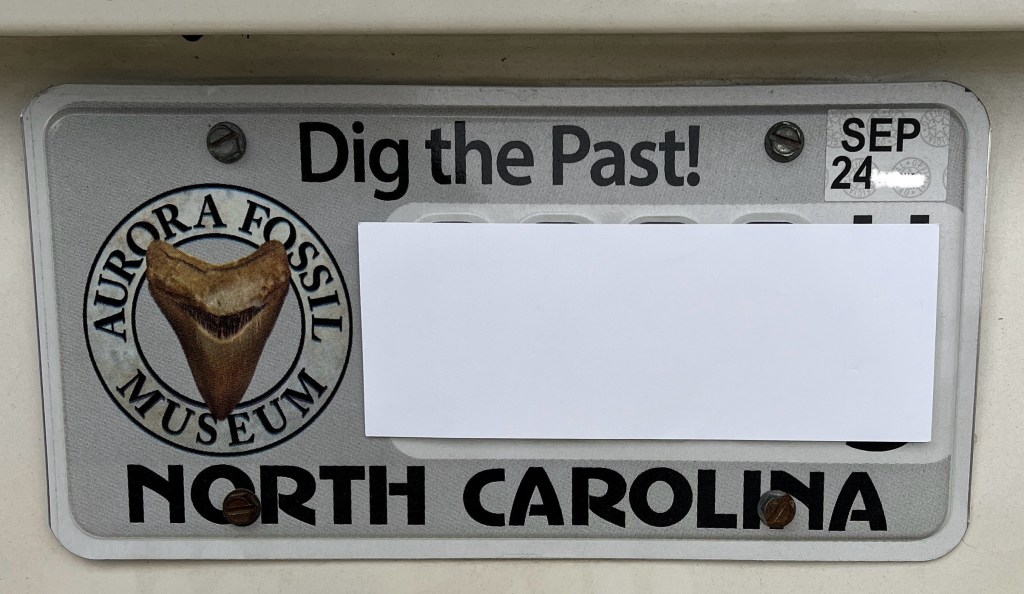

Imagine my delight when I learned last year that the Aurora Fossil Museum had been approved for an official historical site license plate with the NCDMV. I applied for one right away….it finally came, a couple of months ago. I’m among the first to have it:

I imagine Granddaddy’s beaming face. I hear Grandma’s typical expression of surprise: My land!

Dig the Past! the license plate reads.

I do it every day that I live. I go on mining my memories for stories, working their meanings out bit by bit, trying to preserve them for the priceless treasures they are.

Keeping the past alive. For the future. For right now.

That’s what memoir is for.

*******

Composed for Day 30 of the Slice of Life Story Challenge with Two Writing Teachers