I don’t often get reader requests for posts here on my blog, but after sharing an exercise on writing about your past —”When you look back at your life, what do you see?”— a phrase about my childhood home stirred some curiosity and I promised to tell the story behind it.

So if you read Dust motes and asked about “Bullet in the living room rug, in the floor, if you know where to look,” today’s post is officially dedicated to you.

To recollect these details, I had to submerge a good while in Long Ago. When this event occurred I was around eight years old. That part’s blurry.

The rest, however, is all too vivid . . .

Mom lifts the curtain again but there’s only blackness beyond the picture window. I know by her sigh that the street is empty. No sign of Deb. She has never been this late before. She’s usually here before supper but tonight we had to go ahead and eat, hours ago. Baby Aimee—Deb’s baby—is fussy because she’s ready to go to bed and can’t settle. Mom holds her on one hip, says “Shhh, shhh, you’ll be going home to sleep soon.” Something icy glitters in my mother’s black eyes as she looks out of the window into the night.

Aimee’s eyes are almost as black as my mother’s. Big and round. They make me think of Looney Tunes characters when they’re sad, how their eyes go all huge and dark. Baby Aimee’s eyes always look like this, huge and dark, even when she’s standing in the playpen staring up at me in the daytime when I get home from school. She can stand without holding on now but isn’t really walking yet because she’s only one year old. She hangs onto my mother, her cheeks pink and watery, her big eyes shiny.

“Mama,” she cries over and over. “Mama.” And she buries her face in my mother’s shoulder.

I am sorry for Aimee because she’s little and doesn’t understand things yet. I am starting to feel sorry for Mom because it’s not easy to take care of someone else’s baby while they work all day and then don’t show up and you don’t know why . . .

“Mom! What if something has happened to . . . “

She turns on me, her mouth a tight line under those icy-hot eyes. “Shh!” she nearly spits.

And I know, I know why.

Mom’s afraid.

Just then headlights shine through the window. Mom snatches back the curtain. Her body softens like a flower in a glass of water.

“Thank God.”

She squeezes past the playpen—it takes up the most of our living room floor space—and goes to open the front door.

I hear Deb’s laughter before I see her.

Someone is with her.

They come in.

Deb is short with shoulder-length reddish hair and glasses. She dresses in what teachers at my school call “mod.” Sometimes short skirts and boots or chunky shoes, sometimes vests and bell-bottoms. Deb smiles a lot but tonight she can’t stop laughing about something. Even when she says to Mom, “I am sorry it’s so late, had some car trouble…this is Ab. My boyfriend.”

Ab, standing partly behind Deb, is very tall. His face is thin and white, his hair black, curly, reaching past his shoulders. He’s wearing a long fur coat. I’ve never seen a man in a fur coat before. He nods to my mother when Deb introduces them but he says nothing.

Mom looks at me, hard. “Go to bed now.”

I know this really means “I’ve got things to say that you don’t need to hear” and so I head down the hall without a word—

—BANG—

—a flash of light, the loudest sound, thunder in the house, like a car hitting it, shaking it, rattling the windows—

—a scream, not sure whose, my mother’s or Deb’s—

—baby screams—

I run the few steps back to the living room.

There’s a funny smell, something smoky.

Pieces of brown fur, hundreds of pieces, floating through the air.

Deb’s crying now, her screaming baby in her arms. Ab’s face is whiter than before. I stand, frozen, as my mother demands the gun he has in his pocket, or the pocket he had a minute ago, before he blew it to smithereens.

“HOW DARE YOU bring a gun into this house, around other people, around children! To stand here with your finger on the trigger…Give. It. To. Me. NOW.”

And Ab places the handgun in my mother’s open palm.

As her hand closes around it he hurries out of the door, away from her, back into the night.

*******

After Deb and Ab were gone—and after she vacuumed up all the fur—Mom ran her fingers over the rug. She found the hole and the bullet lodged in the hardwood floor beneath. For as long as we lived in that house, I could find the bullet, too.

The house still stands, so as far as I know, the bullet remains there to this day.

I can’t recall what became of Deb and her beautiful baby, Aimee, or how quickly after the bullet they quit coming to our house. I changed their names in case they’re still alive out there, somewhere. I wonder if they are. And what their stories are. And if I could stand knowing.

I really wonder about Ab.

All I know is that my mother kept his gun a long time. I’m not sure she ever gave it back. Or where in the house she hid it. Somewhere far away from children…

I think a lot about the darkness of that night, of a baby’s big, frightened eyes, of being completely at the mercy of others and their choices, not just sweet baby Aimee, long, long ago when I was still a child…but my mother, who didn’t drive, who babysat for many years to make ends meet, who accommodated other people’s schedules and whims, who was dependent on others to go anywhere or get anything she needed. Some might say powerless.

But they didn’t see her take a gun away from a strange man who towered over her, a man who, as far as I know, never darkened our door again.

I did.

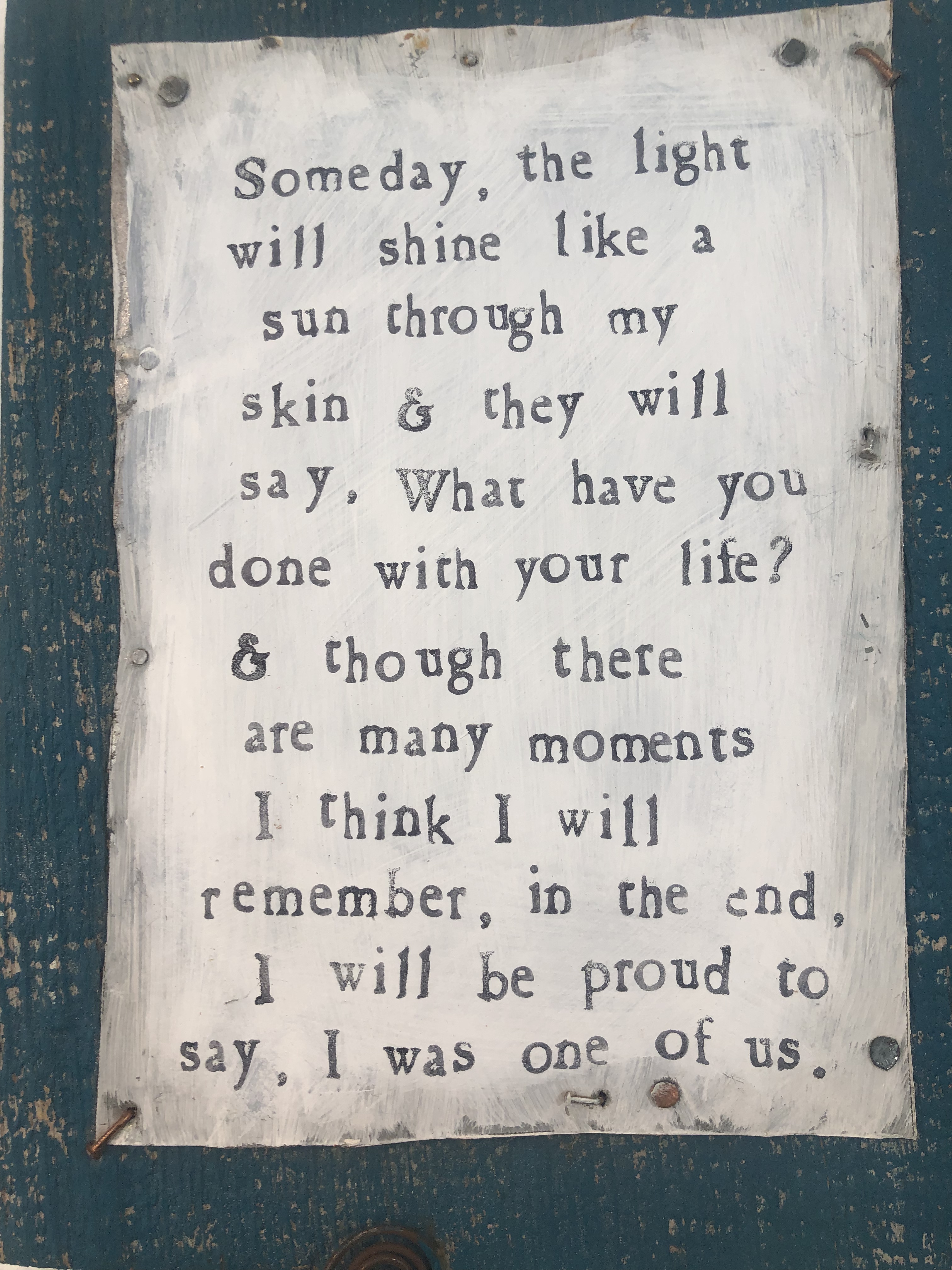

The moment reverberates in my mind still. Lodged deep, so deep in my memory, lying there all this time, covered by layers and layers of stuff …

The power remains, if you know where to look.