Quarterman shipfitter looks at blueprints, 1943. Museum of the U.S. Navy

“Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, compute, and communicate using visual, audible, and digital materials across disciplines and in any context.

The ability to read, write, and communicate connects people to one another and empowers them to achieve things they never thought possible. Communication and connection are the basis of who we are and how we live together and interact with the world.”

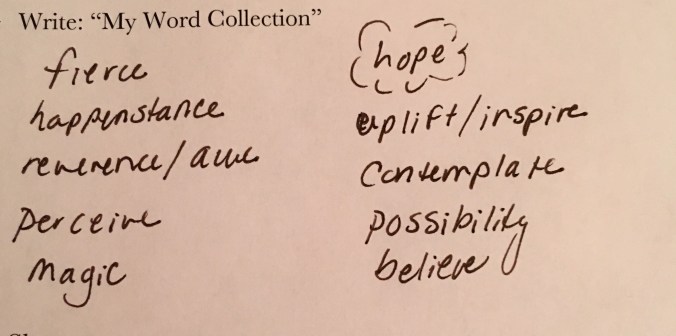

On the eve of the New School Year, I contemplate my role in the scheme of things. In the face of changes in staff, in curriculum, in differing perspectives on literacy instruction.

I am defined by literacy. I’ve loved reading and writing all my life. My professional work is literacy: As a coach, I collaborate with teacher colleagues across grade levels on how to best teach English Language Arts in ways that meet the needs of all students.

When it comes to defining literacy, I rely on the International Literacy Association, for no two dictionaries, and hardly any two people, seem to have the same idea of it. Some believe it’s just reading and writing. But it’s so much more . . . .

In the ILA definition several things jump out at me, beginning with

the ability to interpret

in any context

I think of my grandfather.

Over a hundred years ago, my grandfather left school to work on his family’s little North Carolina farm. He married during the Great Depression. When tenant farming, sharecropping, and other odd jobs like painting houses weren’t enough for him to “make a go of it,” Granddaddy rode with men from his hometown to Newport News, Virginia, in hopes of landing steady work at the shipyard.

Granddaddy became a shipwright, responsible for helping build the keels of ships, less than a year before Pearl Harbor. When America entered World War II, production continued around the clock with the invention of a new thing: aircraft carriers.

He made his living; he took care of his own. He retired from the shipyard when I was five. He and Grandma moved back home and there I spent my childhood summers.

In the evenings he sat in his recliner while Grandma and I sat on the living room floor. She spread the newspaper out on the carpet, handed me the “funnies” section, and then she read the rest of the paper in a loud, clear voice to Granddaddy—his years around industrial equipment in the Yard had made him hard of hearing.

I eventually asked:

—Why do you read the paper to Granddaddy? Why doesn’t he just read it?

—He can’t, Dear.

—Why? Is something wrong with his eyes?

—No, no. He just never learned to read, not much, really. He quit school in the fourth grade to help on his family’s farm, you see . . . .

I was stunned. This was the first time I’d known of anyone who couldn’t read.

It hurt my heart for him.

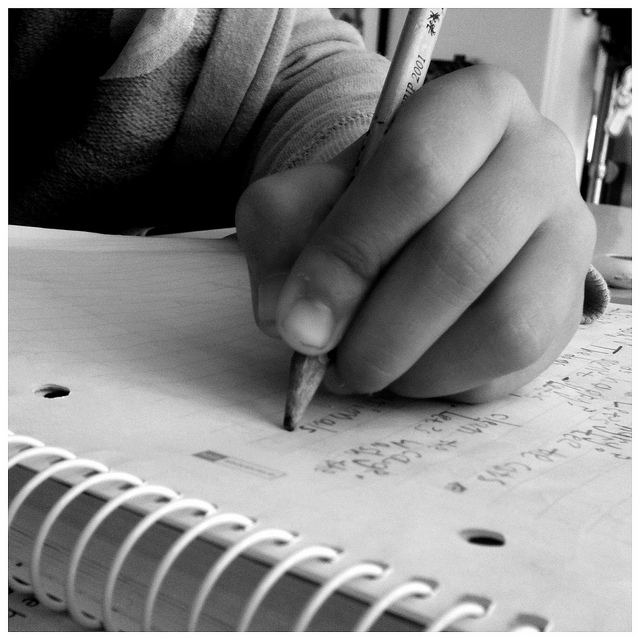

But I later learned that he could read intricate blueprints and build to those precise measurements. That’s what he did at the shipyard all those years.

It’s something I can’t do.

the ability to identify, understand, interpret

using visual

materials across disciplines

and in any context

My grandfather was always a farmer first; he read the days, the seasons, the weather.

He read nature. When he and I came across strange worms gliding over his front sidewalk, he couldn’t identify them but instinctively knew to leave them alone. Decades later I researched them (land planarians) and learned that if he’d tried to crush or chop them up, every piece would have replicated and they would have destroyed the good earthworms that kept his garden so abundant and healthy.

Signs, symbols, meanings, he understood. Not in or from books, but from life. He possessed visual-spatial acuity. Keen intuition. He read the times in which he lived, comprehended that the way of life he and the generations before him had known was passing forever. He reached for better things. He worked hard. He collaborated with a lot of different people. The shipyard management eventually asked him to be a supervisor, and that’s where his courage ran out. It required regular paperwork. He declined the position.

My heart ached again, deeply, on learning that.

The ability to read, write, and communicate connects people to one another

and empowers them to achieve things

they never thought possible.

That belief is behind everything I do with teachers and students.

The greatest man I’ve ever known indirectly taught me, years ago, that reading and writing are the keys to opening doors of possibility and opportunity. He also taught me that literacy is so much more, long before this digital age.

We have to be able to read words and ascertain their meaning, but our survival depends on more. We must be able to read the times, read people, read what we see, what we are creating. And make sense of it. We must interpret. That’s the entire, inherent value of reading and writing in the first place.

We must communicate well with one another, recognizing that each of us possesses different strengths, all of which are valuable to helping each other. Communication is the keel on which all good relationships are built. We must speak, but we must listen more, absorb more, understand more.

Communication and connection are the basis of who we are

and how we live together

and interact with the world.

My grandfather survived—his family survived—because of his clarity of vision and sense of purpose. He knew he lived through unique times. In his last years he preserved his life experiences for future generations not by penning a memoir but by recording his stories on a set of audiotapes. I don’t think he ever knew just how unique, how extraordinary, he was. In my mind I see him now—thick white hair, plaid shirt, gray pants with a black belt, black shoes, his big, wrinkled, work-worn hands folded in his lap, leaning back in his recliner listening to my grandmother reading. In addition to the nightly newspaper, she read the Bible through to him each year.

And so, on the eve of the New School Year, I contemplate my role in the scheme of things. I think of the constant adaptation of teachers to the times and the changing tides of literacy instruction; of students, each of whom has strengths and gifts that may not be obvious at first. I think of their futures and know that clarity of vision and a sense of purpose are vital to their learning and well-being. To all of our well-being. I think of my grandfather reading complex blueprints and going forth to build something previously unknown in a vastly changing world. I think about life literacy as well as literacy for life. How we live together and interact with the world.

For, in truth, we are building the world.

*******

Here’s the story of Granddaddy and me encountering those unknown worms long ago: First do no harm.