The National Day on Writing invites me to examine my writing history: Why DO I write, really? And why do I love it?

I don’t know exactly when the desire began, only that it manifested itself early in life.

It had nothing to do with the hateful formation of letters on paper. My handwriting was never pretty. Even now my letters aren’t uniform; I scrawl my thoughts onto a page lightning-fast, before they escape me.

That’s what writing is. Thoughts. Ideas. The attempt to capture and convey images, emotions, sensations.

It has everything to do with words.

I fell in love with words long ago on my grandmother’s lap as she read book after book to me, the prosody of her voice like the waves of the ocean rolling on and on and on. Endless, musical, alive. Her voice buoys me to this day. I hear it still; she is never far away.

At age six I gathered paper and a pencil, sat at the coffee table in my living room, and wrote a story that I’d heard many times. No one said Do This. The compulsion came from within. The writing was for me and no one else. It simply needed to be done and I wanted to do it. So there I sat, laboriously printing my ugly letters, making words to what I believed was the most beautiful story in the world.

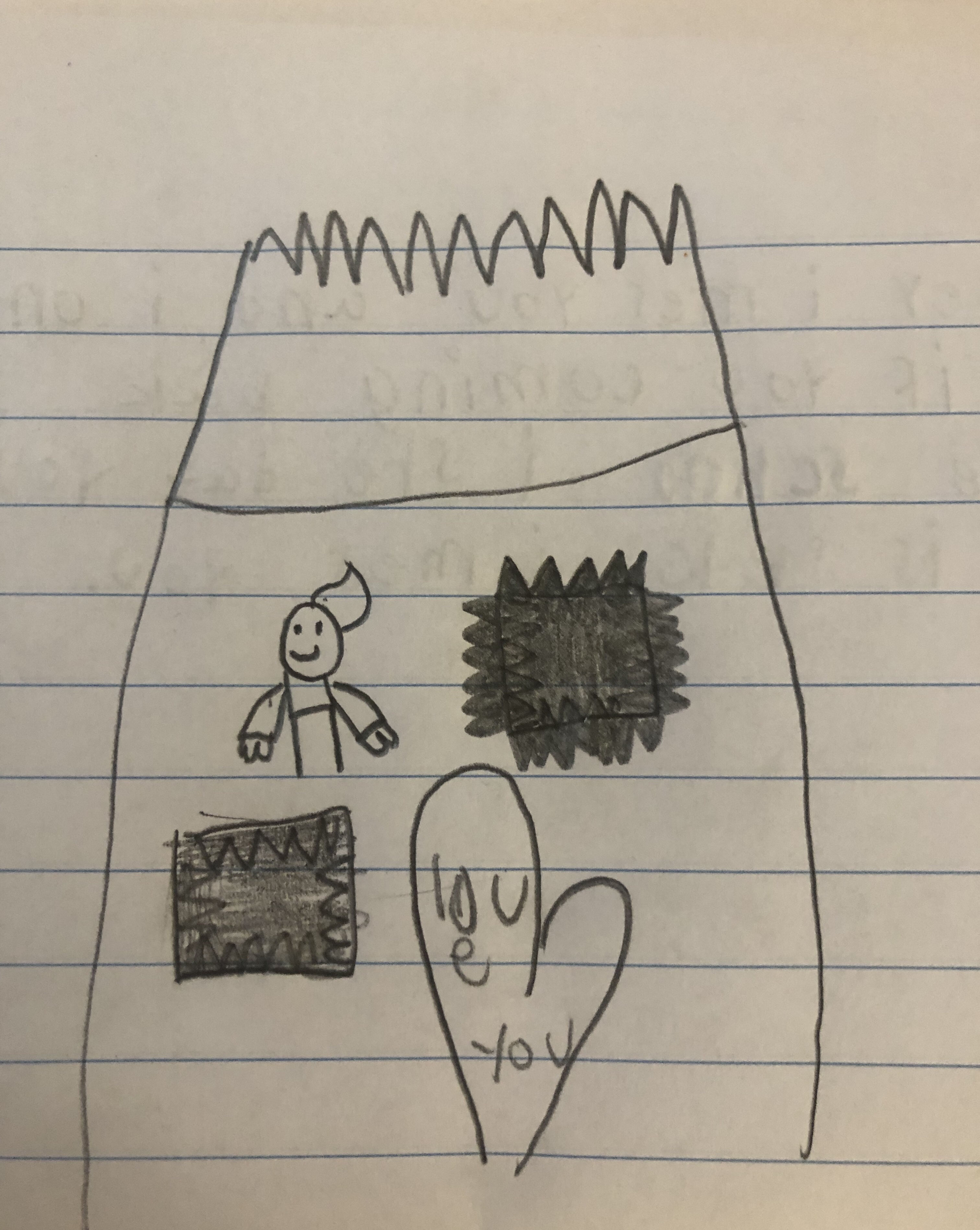

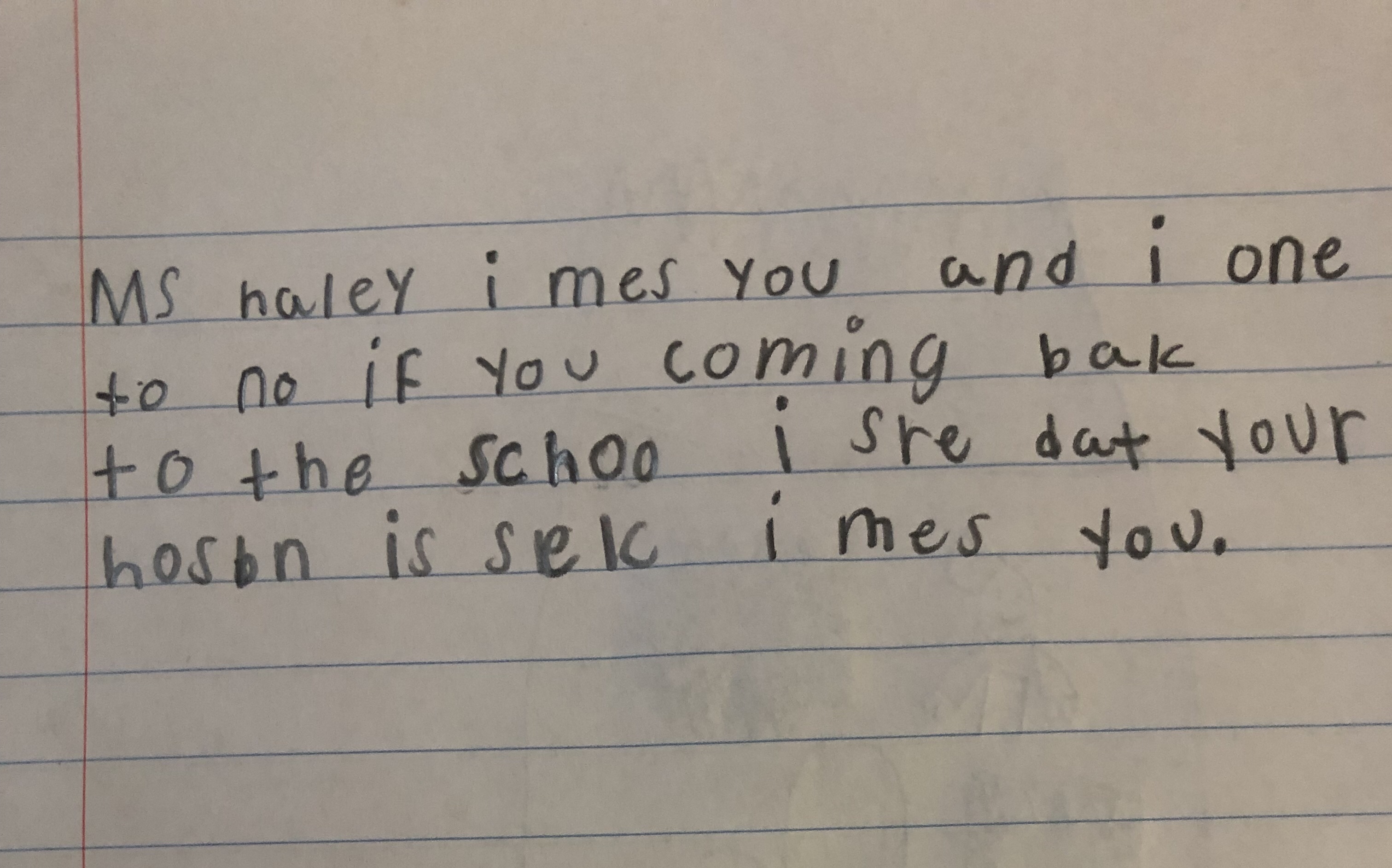

I wrote because, in the days before the Internet and cellphones, Grandma wrote letters (with perfect penmanship) in which she included books of stamps so that I could mail letters back to her.

In my adolescence she gave me a diary with a lock and key (two keys, actually, in case one got lost). I flooded those pages with the secrets of my young soul, such as the angry suspicion that my parents had adopted me, whereas my sister was their real child, and: One day I want to write a book. I hope it will be published!

And so I wrote.

One teacher, then another and another, strategically placed throughout my education, said Keep writing. Here’s what you do well. Here’s a thing that can make your writing even better. They asked me to read my work to my classmates, who said Keep writing. Oh, and will you help us?

Throughout my teens poetry called to me. It said: You hear my music. Show me. Come, dance. Don’t think about perfect steps. Just listen and follow what you hear.

—That’s pretty much how I write everything now.

And the books, the books, the books . . . who and what would I be if I had not loved reading so? All genres, all my life. New words, new information, new ways of thinking, new things to explore and imagine. New motivation to write with the same power as the writers who stir something my very core, as our cores are clearly made of the same stuff.

So, to this day, I write. Because I love story, real or imagined. I write with and for children who have their own stories to tell. I write to cope with people and situations that I cannot change and to remember all that’s good in my life. I write my celebrations and my losses. I write not to wage war on the world but to find peace in myself, where finding peace with others begins. I write to forgive myself and others. Not with words that destroy, but those that build, that create, that go on in the belief that the chapter to come will be better than the one before. Even when pain is woven through it, so is joy. Because that’s life. And love. And writing. I want to store it all it before the hippocampi in my brain (I envision these as two seahorses, yes) stop recording my memories and before the ideas evaporate and the words don’t come any more.

Until then, on a sea of words, the rhythm of life rises, falls, and calls: You hear my music. Show me. Come, dance. Don’t think about perfect steps. Just listen and follow what you hear.

And so I do, with a heart full of gratitude.

That is why I write.