public scare

shelves are bare

everywhere

germ warfare

must beware

tempers flare

sad affair

be aware

none to spare

it’s unfair

selfless share

would be rare

do we dare

do we care

nothing there

say your prayer

public scare

shelves are bare

everywhere

germ warfare

must beware

tempers flare

sad affair

be aware

none to spare

it’s unfair

selfless share

would be rare

do we dare

do we care

nothing there

say your prayer

I am not sure what inspired me to write this poem as a teenager. Likely it was born from a love of fantasy and mythology. Perhaps I was just playing with rhyme. Maybe I was feeling silly. Or all of the above. The only thing I’ve changed from the original is some punctuation.

Nevertheless, consider yourself forewarned, should a baby dragon drop in to visit YOU …

Once, a baby dragon

dropped in to visit me.

He flew right through my window

(he’s not too bright, you see).

He was quite a charming fellow

with enormous, greenish scales,

quite polite, this dragonlet,

who came to hear my tales.

I told him one of Pegasus,

the horse with wings of gold.

I told him one of Camelot,

of days when men were bold.

The dragonlet, he loved these tales!

He begged and begged for more;

once he laughed so very hard

he burned down my front door.

I told him of the Lion King

who secretly had sworn

not to tell the whereabouts

of the only Unicorn.

When morning’s light awoke me,

the dragonlet had gone.

The only trace I found of him

was on my neighbor’s lawn.

Photo: Baby dragon. Derek Hatfield. CC BY

In late February, we had our only snow this winter.

I woke in the morning to find the sun shining through the crape myrtle I planted when we first moved here. Ice crystals glittered on the tree limbs like a thousand prisms—tiny, brilliant rainbow lights. I took a picture. When I looked at the image, the word that came to mind was holy.

Maybe it was the brightness of the sun. The reaching ray of light. The purity of snow. The hush, the stillness. Just a sense of divine glory, of peace.

And then I noticed where that sunbeam ended.

Oh, how I recalled, in that instant, first reading Where the Red Fern Grows when I was around ten years old. It tore my heart out. I wept for weeks. A dog story, of course. And hardship, love, and sacrifice. Wilson Rawls wrote:

I had heard the old Indian legend about the red fern. How a little Indian boy and girl were lost in a blizzard and had frozen to death. In the spring, when they were found, a beautiful red fern had grown up between their two bodies. The story went on to say that only an angel could plant the seeds of a red fern, and that they never died; where one grew, that spot was sacred.

That’s when the boy, Billy, finds a red fern growing between the graves of his two dogs.

Look where my sunbeam ends.

Directly over the grave of my family’s little dachshund, Nik, who was with us for sixteen years. That’s his memorial statue rising up from the snow.

No red fern, of course.

But sacred, just the same.

I had my first check-up for my broken foot.

“Ah,” said the orthopedist, displaying the X-rays, “this is excellent progress.”

I breathed a little more freely.

I knew it was better. I’d walked on it a little at home—just a little—without the boot, without pain, even though I wasn’t supposed to.

What concerned me most was … well … I am growing older. All I did was fall off of three garage steps and the bone just snapped.

Are my bones becoming fragile?

“It’s a common break,” said the tech. “What’s not common is the complete break. Usually it’s a fracture. Yours is a hurty one.”

“Yeah, it hurt plenty in the beginning,” I replied, “but not now. This progress means my bones are good and healthy, right?” Translation: I’m not decrepit, yet?

“They’re very good,” smiled the orthopedist. Who looks about fifteen.

He graduated me to an orthopedic shoe. But still no driving for four more weeks. State law says not while I require “medical equipment” on my gas foot.

<sigh>

But, I have good bones.

I examined them up on the screen. Marveled at how much the broken one had already knitted itself back together in just three weeks. Amazing how bones can even do that.

“That’s the best part of this particular field,” said the orthopedist. “Getting to watch people heal. Oh, and you can walk some in the house without the shoe. Movement stimulates bone growth.”

He looked at me knowingly.

I just smiled.

Walk to knit, knit to walk …

Rather meta of us, don’t you think, my little metatarsal.

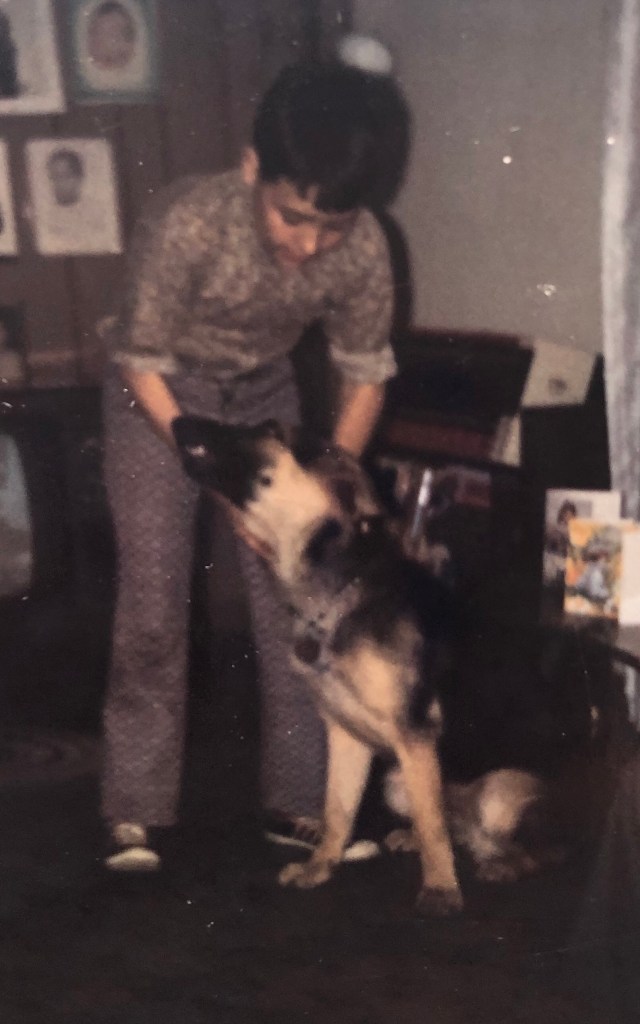

A good dog is one of life’s greatest gifts. Today’s post is dedicated to Rin, my husband’s childhood pet.

Dear Boy,

It is late. I am thinking about you sleeping upstairs. I wish I could get up there like I used to; I feel I should be near you tonight.

But I content myself with knowing that you are here and safe.

I think about the first time I saw you.

There you came with your mom and dad, looking at all my brothers and sisters at the place where we were born. As soon as I saw you, I knew: That is my Boy. That is my Boy. I ran straight to you, your arms went around me, and that was the moment we began. How excited you were to give me my name. Rin Tin Tin, you said. He was famous and you look just like him!

I was just happy because you were happy.

Do you remember taking me to classes? I do. How proud I was to learn what you wanted, to make you so pleased with me.

I’d do anything for you, my Boy. I hope you know.

I remember that bad time when I was still a very young dog and you were so sad. When your dad left for work and never came back. I knew you were hurting and afraid; that’s why I stayed so close. I gave you all the comfort I knew how, the warmth of my body, the occasional lick for reassurance. I watched you while you slept in case you woke and needed me.

You’re my everything, Boy. You always were.

Remember how you’d throw a stick for me to fetch, over and over and over, because I never got tired of it? How I miss that! I will still fetch for you, Boy, if you would only let me. That’s why I keep finding sticks and bringing them to you even though I understand you don’t want me to run. I know I am slow and yes, it hurts my old hip—but it is what we do. It is what we always did. So much fun, so much joy. If I could have fit your basketball in my mouth all those hours and days and weeks and years you were out on the backyard court, I’d have played that with you, too. But it was enough for me just to run beside you.

Perhaps tonight I will dream of those days, when we ran and ran and you got tired but I never did. I am tired now. I want you to know that whatever comes, Boy, I would do it all again. Every bit of it.

You’re my life, Boy. I love you so.

Now I lay me down to sleep. I’ll wait for you in the morning.

Goodnight, Boy.

Rin

*******

On the morning after the Boy and I got married, his mother found Rin unresponsive. He’d had a stroke. He died later that day at the vet’s office.

He was thirteen.

—I’ve always believed you knew that you finished your job, Rin. You saw the Boy safely off to his adult life on the last day of your own. Thank you, Rin Tin Tin, good and faithful servant, for giving him your all.

The Boy loves you still.

On the way to a required professional development session, my colleague and I stopped for coffee (me) and Diet Coke (her).

“Gotta have something to keep us awake,” we told each other.

Upon arriving at our destination and settling in, I began looking over the materials, took a sip of my coffee, and—

“Good HEAVENS, that’s sweet!” I spluttered. I haven’t had sugar in my coffee in years, just two creams. Perhaps that’s why the taste was so intense?

And then I saw the tag on the cup.

Friends, and we wonder what is wrong with our country.

Today’s post serves a dual purpose: My daily Slice of Life Story Challenge and Spiritual Journey Thursday, organized by my friend Margaret Simon on the first Thursday of the month. Thank you, Margaret, for the invitation to host.

I chose to write around the theme of “balance.”

Not necessarily what you may think…

*******

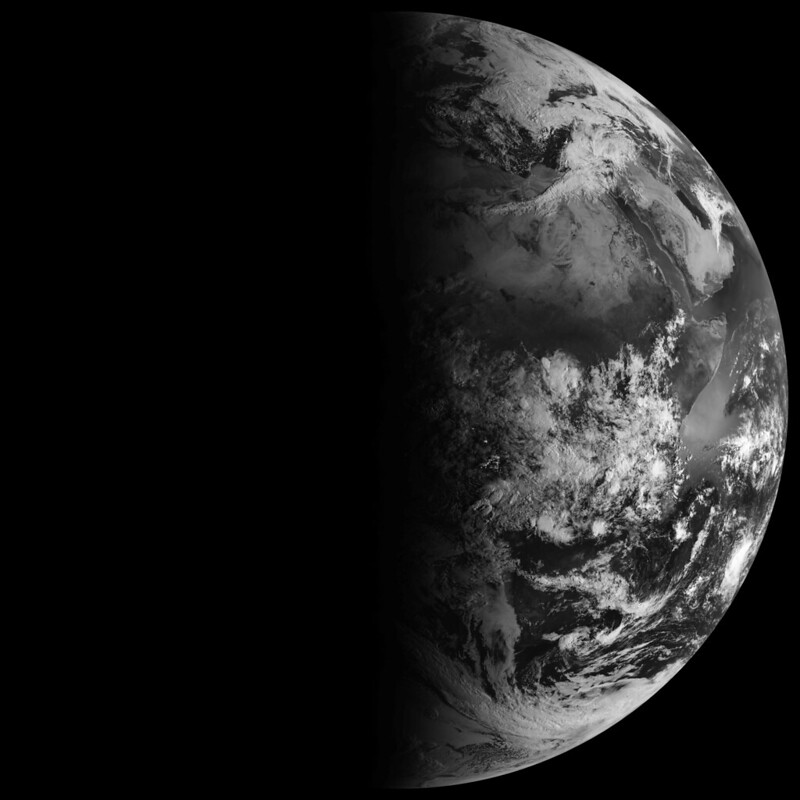

It’s almost here.

Spring. The equinox.

A balance of light and dark in the world, or “equal night.”

My thinking radiates in a number of metaphorical directions here but I’ll begin with the moment I was at school grappling with a new data reporting system that I have to teach to colleagues. I logged in and discovered this message: Alternate Data Entry for Dark Period.

Dark Period?

It has the sound of a span in history, like it belongs in the Holocene Epoch of the Quaternary Period, the current one in which we live, geologically speaking (“current” meaning over 11, 000 years old, for the record). As if it can be marked in time like the Ice Age or at least the Dark Ages.

Dark Period.

All it means, apparently, is the time when the data reporting system is shut down to be updated. It’s tech housecleaning. During the Dark Period, no additional data entry can occur, until everything is verified and balanced.

The words stuck with me, though.

Many would say we are living in a Dark Period now. It’s an era of strife, vitriol, backlash. An age of ever-increasing concerns over mental health. Over health in general—the coronavirus.

And at the heart of the darkness is fear.

A. Roger Ekirch writes in At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past: “Night was man’s first necessary evil, our oldest and most haunting terror. Amid the gathering darkness and cold, our prehistoric forebears must have felt profound fear … that one morning the sun might fail to return.” He goes on to say that many psychologists believe that our early ancestors feared not the dark itself but harm befalling them in the dark (for it was an unlit world at night) and over time night became synonymous with danger.

Fear leads to anger and anxiety. In the dark, things don’t look as they should; they’re distorted.

What’s the balance?

Now we’re back to the equinox, metaphorically.

Light. Day. The assurance that there’s still good working in the world, undoing harm. Think of the destruction of Australia and the human involvement in deliberately setting bushfires. Then think of soldiers in the Australian army, lined up in rows, cuddling and nursing koalas when off duty. Then apply it to people suffering around our globe …

We are our own greatest enemy and helpmeet. We all hang in the balance of these: despair and hope, destruction and edification, hurt and healing.

In The Forgotten Beasts of Eld, Patricia A. McKillip describes a monstrous creature like “a dark mist” who embodies “the fear men die of.” The novel is about learning how to live and love in a different world.

That would mean overcoming the dark, the fear.

Incidentally, in a strange balance, the current virus causing so much alarm shares its name with the crown of the sun.

And, speaking of the sun, here’s the secret of the equinox, why it’s not really equal: There’s actually more day than night.

More light. Literally.

And figuratively, it has nothing to do with moving around the sun and everything to do with moving the human heart.

Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. CC BY

*******

Dear fellow Spiritual Journey Thursday sojourners: Please click the link to add your post to the “party”:

https://fresh.inlinkz.com/party/f941589ea3ed4e83be8dd519044d3bfd

Memoir is probably my favorite kind of writing.

It’s like small moments on steroids. When I write myself back into childhood, scenes, conversations, little forgotten details are pumped full of meaning, for I have the advantage of understanding so much more than I did then . . .

This event occurred when I was seven or eight. As I write, I think of how we don’t know all that children are experiencing or how they’re trying to navigate life. Families don’t make perfect portraits. There are so many reasons why.

We are our stories.

With that in mind I’ve opted to change family names here. It gives me the final shot of courage needed to share “Spittin’ Image.”

*******

We are going to visit my grandfather.

Not my Daddy’s daddy, my Sunday-afternoons-in-the park Granddaddy who bought me red rubber boots when I started school because all my kindergarten friends had them and I wanted them, too. We are going to see my Mama’s daddy. I don’t know him very well. He came to visit us once, sat in our living room chair with his hand stuck out so that when I ran by, not paying attention, not being careful, his cigarette burned me.

Mama says he lives in a hospital.

I don’t know why anyone would live in a hospital. I don’t want to go see him, don’t know why we have to go.

My mother gets snappy: “He’s your granddaddy—you’re going!”

My aunts are taking us because Mama doesn’t drive. She doesn’t know how.

“Last time I seen Daddy, he was looking better,” says Aunt Bobbie, who’s driving us in her maroon Ford LTD, a Marlboro sticking out from the first two fingers of her right hand on the steering wheel. I see her mouth in the rear-view mirror. There are little pucker lines around her lips. “I believe he’s eating good. Acted happy to see me, too.”

Aunt Imogene—Genie, I call her—is riding shotgun in front of me. She takes a long drag on her own cigarette. I slide over so I can see the thick white smoke pouring out of her mouth and how it all goes right up her nose, like a waterfall in reverse. It’s neat to watch. About ten minutes pass before she speaks; Genie never does anything fast.

“Waaaay-yelllll…” says Genie, stretching the word well into four or five syllables, “at least we know he’s taken care of at the Home.”

Beside me in the backseat, Mama puts a Salem Menthol in her mouth and flicks her lighter, inhales. She doesn’t do fancy stuff with her smoke. She is quiet.

She is often quiet.

The ride takes forever. Finally Aunt Bobbie says, “We’re here,” and we pull into a parking place bordered by pine trees.

Mama drops the butt to the ground and grinds it into the gravelly dirt with her sandal. This is my grandfather’s Home, I guess, but Mama told me it was a hospital, so I’m confused. When we go in there are many small rooms but no bright lights, no doctors in lab coats, no nurses wearing white dresses and little caps. There’s a lot of wood paneling. The Home makes me think of a really big cabin but the people here don’t look like campers. Some are in wheelchairs, some are standing. Some are in pajamas. Not all of them are old. They stare at us as we go by and I don’t like the feel of their eyes.

Aunt Bobbie leads the way, down a hall, around a corner. I peek in one room and see a man with long white hair lying in bed with his mouth open, but he’s not asleep.

I want to run out of here.

Genie says, “Waaaay-yelll, hey, Daddy.”

He’s sitting in an armchair in a little living room area, holding a lit cigarette in the first two fingers of his right hand. All of his fingers have yellow stains. His nails are brown and long, and the ashes on that cigarette are the longest I’ve ever seen; why don’t they fall?

Genie hugs him. Aunt Bobbie hugs him. He says “Hey” to them in a high, raspy voice. He doesn’t have much hair. His face is long, kind of yellowish, kind of gray, with brown spots. His clothes have spots, too, except that they’re actually small holes. From dropping cigarettes. Or ashes.

Mama is hanging back but Aunt Bobbie pulls her over.

“Daddy, look who come to see you. Beverly Ann.”

“Hey Daddy,” says my mother, bending to hug him, then stepping back. “How are you doing?”

My grandfather looks at her, his daughter, my mother, and I can tell he doesn’t know her.

Next thing I know, she’s yanking on my arm.

“I brought your granddaughter to visit.” She tugs. “Come on, give your granddaddy a hug.”

I do not want to. I don’t move. I just look at him.

Genie pokes me from behind.

“Go and see him,” say my aunts. “He’s your granddaddy.”

I already see him and he sees me. For a minute I look into his eyes—they are big, green like moss—and the emptiness there makes me think of a hole in the ground that has no bottom. Or the time Daddy was holding me when he opened the medicine cabinet and its mirror reflected into the mirror over the sink. Mirror, mirror, on the wall . . . it became a mirror, mirror, mirror hall, reflected mirrors going on and on and on, growing tinier and tinier, like a never-ending nothingness. I’m frightened of my grandfather’s eyes, frightened that he’s looking at me with them, that something about them makes me think of my mother.

Then they light up. He knows me! He holds out his hand—not the one with the cigarette, I have my eye on that one—and calls to me:

“Beverly Aaaannn…” he says, drawling like Genie does.

“No, Daddy,” says Aunt Bobbie, “this is Beverly Ann’s daughter. That,” she points to Mama, “is Beverly Ann.”

He keeps right on staring at me.

He doesn’t get it. He thinks I am my mother. When she was little.

I hug him because I have to, because the sisters, his daughters, are making me. His skin is cool and frog-like. When I pull away, he’s still looking at me.

Am I supposed to love him? I don’t know him. And he doesn’t know me.

We don’t stay long. As soon as we’re outside, Genie bums a light off Mama, who’s shakily firing up another Salem. Genie sucks deep, does her dragon-smoke thing, nods at me.

“I’ve said it a thousand tiiiiiimes, you are your Mama’s child, that’s for sure. Spittin’ image.”

“Ain’t she though?” agrees Aunt Bobbie.

I walk beside Mama. The aunts move ahead of us. Hoping they won’t hear, I whisper: “Why did he think I’m you, Mama?”

“His mind’s not right. Never has been,” she says, taking a drag, looking off in the distance at nothing in particular. “I really wasn’t around him much. I was a little girl when he left home.”

“Why did he leave?”

She turns her eyes on me. Dark brown eyes, like mine, and for a second they have that bottomless look. She’s slow to answer but not in the way that Genie is slow to do things. She takes another long drag.

“Grannie sent him away because he tried to hurt her.”

“Were you sad?”

“No.” Then, softly: “I was scared of him.”

Aunt Bobbie cranks the maroon LTD; Genie is getting in the front passenger side. Mama looks back at the Home and I wonder what she’s thinking. As I reach for the door, I catch my reflection in the backseat window. I glimpse the pines and the cloudless blue sky behind me. Crows fly overhead, cawing loudly. Yes, I do look a lot like my Mama. Even I can see that.

I feel shaky, too. I lean in to look closely at my own eyes, hoping to God I never find them so empty.

Ever wish you could keep a small child safe and innocent forever? It’s a wish as ethereal as bubbles in the wind, drifting away like childhood itself. I took this photo last summer. It’s taken this long to figure out how to convey what I felt.

Little girl

blowing bubbles

in the sun

free of troubles

How they drift

on the breeze

turning, turning

as they please

Colors shimmer

ever bright

just a moment

in the light

Wave your wand

my temporary

iridescent

bubble fairy

All too soon

time shall pass

bubbles pop

in the grass

How I wish

things could stay

idyllic as

this summer day.

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts…

—Shakespeare, As You Like It

Life’s transitions tend to sneak up on us.

For example, when it dawned on my oldest son that high school wouldn’t last forever and beyond it was college plus this thing called The Rest of Your Life, involving responsibility and duty, he looked at me with big brown eyes full of gloom: “I don’t want to grow up.”

Alas. It happens.

But he found his way. Last fall he simultaneously started the pastorate, married, and became the dad of a beautiful four-year-old girl. That’s a lot of transitions in one fell swoop, and he’s embracing them all. He’s thriving.

One man in his time plays many parts . . .

All of a sudden, his father and I have reached the grandparent stage of life. While it’s the loveliest transition, I can’t keep from thinking, with a pang, How did I become this old? Truth is, there’s exactly the same age difference between my grandmother and me as there is between me and my new granddaughter. It shouldn’t seem so astonishing.

The hardest transition isn’t mine, however. It’s my granddaughter’s. She loves to come over, loves to climb in my lap with a book as much as I loved climbing into my Grandma’s with one. All of this is glorious fun. No, the hard part is what to call me. She’s used to saying Miss Fran:

“Miss Fran, I’m hungry!”

“Oooo, Miss Fran, I like your nails. Can you paint mine?”

“Can we have a popcorn party and watch Frozen again, Miss Fran?”

“Let’s go outside and blow bubbles, Miss Fran!”

She likes telling everyone that I am her grandmother now. She even likes pretending to be me. My son said that after I broke my foot she went clomping around their house with one rain boot on, saying “I’m Miss Fran!” Yikes.

This transition away from Miss Fran has proved challenging. But she’s working on it.

The other night she asked me to spell words for her with magnets on a whiteboard. I did, without realizing that she intended to copy them with a marker.

Here she is, writing with utmost care. A message to me.

With my new name, for the new role I get to play in her life:

Franna.

Life just gets grander.

I asked her if she wanted to spell “Franna” with one ‘n’ or two. She chose two.